“Discrimination Happens Anytime, Anywhere”

Dr. Akira Horii

Born in October 1931, Vancouver, British Columbia

Moved to East Lillooet, British Columbia in 1942, returned to Vancouver in 1949

Retired medical doctor

Parents from Wakayama Prefecture

A Time Without Discrimination Against Japanese Canadians at School

“My childhood was spent in Vancouver, and back then, I didn’t know what discrimination was,” Dr. Horii began. Like many other Japanese Canadians living in Vancouver, he attended Strathcona Elementary School.

At the school, British-origin students were known for a sense of superiority, often used derogatory terms for their Chinese, Italian, and Jewish classmates. However, “I never heard anyone call us ‘Japs,’” he recalled. He estimates that about 50% of the students were Nisei, or second-generation Japanese Canadians.

During that time, World War II had started in Europe. A teacher at the school taught students how to knit socks and make quilts for children suffering in Britain. “Before the (Asia-Pacific) war, I was just a happy kid. I didn’t even know what discrimination was,” he reflected.

The Attack on Pearl Harbor That Changed Everything

Dr. Horii’s carefree childhood was shattered on December 7, 1941, when the Japanese military attacked on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. “The world changed. It turned upside down for Japanese Canadians.” he said. On the same day, Canada declared war on Japan.

Dr. Horii was 10 years old at that time. After the attack, everything changed suddenly. “All of a sudden, we had to quit school. Until Pearl Harbor, I was in Grade 5 in Lord Strathcona Elementary and Grade 5 at the Vancouver Japanese Language School on Alexander Street,” he said. Around 630 Japanese Canadian students were forced to leave Strathcona Elementary, cutting its enrollment in half.

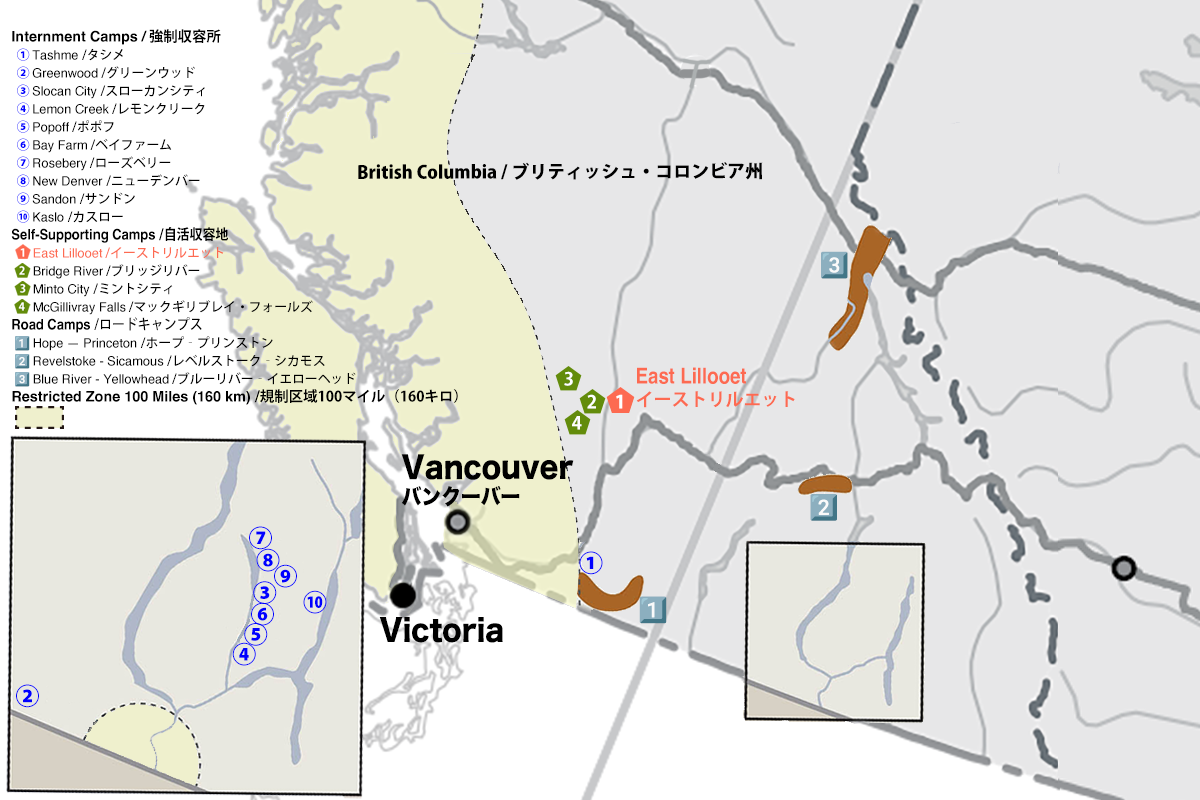

He recounts the events that transpired within the Japanese Canadian community. The Canadian government mandated that all Japanese Canadians, regardless of citizenship, relocate from British Columbia’s coastal areas to locations at least 100 miles (160 kilometres) inland. Homes, cars, businesses, fishing boats, properties and other possessions were confiscated, including the fishing boat owned by Mr. Horii’s father. Able-bodied men aged 18 to 45 were forced into road labour camps at one of three sites in BC: Hope-Princeton, Revelstoke-Sicamous, or Blue River-Yellowhead. Those who refused road camp work were sent to prisoner-of-war camps in Ontario.

The Canadian government established ten internment camps in BC: Tashme, Greenwood, Slocan City, Lemon Creek, Popoff, Bay Farm, Rosebery, New Denver, Sandon, and Kaslo. Sandon, a remote valley town with harsh winters, housed a significant Buddhist population. Many internees later relocated to New Denver. “These ten sites were government-supported internment camps,” he explained.

On January 14, 1942, the Canadian government designated Japanese Canadians as “enemy aliens,” and by February of that year, the forced relocation to internment camps had begun. Since the ten designated camps were not ready, many people were initially sent to Vancouver’s Hastings Park, where they lived in horse stalls that reeked of urine and feces. “I’ve heard that some people stayed there as late as September or October,” he said.

In addition to government-supported camps, there were also “self-supporting sites” where people lived without government assistance. Four such communities existed in BC: East Lillooet, Bridge River, Minto City, and McGillivray Falls. These sites received no government aid, requiring residents to be self-sufficient. However, families were allowed to stay together in these locations.

Life in East Lillooet

Dr. Horii began, “My parents decided to move to a self-supporting internment site.” They traveled by ship from Coal Harbour to Squamish, where they transferred to the Pacific Great Eastern Railway (PGE), now known as BC Rail. He recalls that Squamish was the southernmost terminal of the PGE at the time. After the transfer, they arrived in Lillooet the following morning. “I got up in the morning, and, we were surrounded by mountains,” he said. “I thought, “I thought, ‘Oh, gee. This is where we’re going to live.’ And I thought maybe it won’t be so bad living in this little town called Lillooet.”

However, he added, “to my surprise,” they were taken further by truck, crossing the Fraser River to a place called East Lillooet, about four miles (6.5 kilometres) away.

In the spring, his father and other men in the group began constructing tar-paper shacks. His mother, meanwhile, was busy caring for Dr. Horii and his four younger siblings. “There was no drinking water, no electricity, and no jobs because of discrimination,” he explained, as Japanese Canadians were even prohibited from entering the town of Lillooet.

Despite these hardships, families found ways to survive. Drinking water was purchased, and they built a filtration system to use water from the Fraser River for household needs. They grew vegetables such as potatoes, onions, and even burdock root (gobo). They raised chickens for eggs and sometimes bought salmon from Indigenous people. “My mother canned the salmon,” he added. Each family also built a bathhouse, allowing them to live self-sufficiently.

Many of the men relocated to East Lillooet had been fishermen, and there were few opportunities to earn a living. “The saviour for us was Tokutaro Tsuyuki, a farmer from Haney (Maple Ridge),” he said. Tsuyuki recognized that the hot, dry climate of the Lillooet region was ideal for growing tomatoes. The community began cultivating tomatoes collectively. Initially, the harvest was shipped to New Westminster, but they eventually established a tomato canning factory in the town. “That’s how we managed to survive in East Lillooet for seven years,” he added.

Life was difficult, but the men built a small elementary school for the children. “Since there weren’t any teachers, anyone who had graduated high school became a teacher for the younger kids,” he said. However, teenagers already in high school when they moved to East Lillooet couldn’t graduate initially because they weren’t allowed to attend the town’s high school.

By 1946, they were permitted to enroll in Lillooet’s high school. Dr. Horii attended, cycling the four miles to and from school daily. “In the coldest day of winter, the road was covered in ice, and when we get to the high school in town, our mouths will be covered in an ice, frost,” he recalled.

While attending high school, he worked part-time to help support his family, taking jobs at the town newspaper, on his father’s tomato farm, and at the canning factory. “It was only natural for the Japanese eldest son to help the family,” he said.

During his senior year, he returned to Vancouver to attend the UBC High School Conference with a Canadian classmate. Even as a school representative, he was required to obtain a police permit. “To come back to my birthplace Vancouver, I had to get RCMP permit. Because I’m not allowed on the coast,” he added. One evening, while walking on East Hastings Street after seeing a movie, a police officer stopped him. “I think he realized I was Japanese,” he recalled. When asked what he was doing there, he showed the officer his permit. “I’ve got a special permit to come to Vancouver,” he said. In December 1948, Vancouver was still unwelcoming to Japanese Canadians.

In 1949, Dr. Horii graduated from Lillooet High School.

Graduating from UBC Medical School While Working as a Fisherman

On April 1, 1949, the internment policy ended, allowing Japanese Canadians to move freely. That same year, Dr. Horii graduated from high school and enrolled at the University of British Columbia (UBC). “My parents allowed me to go to university,” he said. However, he was keenly aware of the financial burden. “I stayed in a dormitory,” he added, “but to save the 10-cent streetcar fare, I hitchhiked to campus.”

He took six courses per term, even though the standard load was five. “As a freshman from rural Lillooet, I was pretty naive,” he admitted with a laugh. His demanding schedule included chemistry, physics, and biology labs. “When I finished my first year and passed the exams,” he said, “I was amazed that I did okay.’”

Despite this success, he took a leave of absence after his first year to help his father. “My father really wanted to return to fishing,” he explained. Beginning in 1950, Dr. Horii worked as a fisherman, joining his father in salmon fishing near Prince Rupert in northern British Columbia. For two years, he embraced the fisherman’s life, handing over his earnings his parents. As the eldest son, he felt it was his duty to support his family. By 1951, the family had returned to Vancouver.

After two years away, he resumed his studies at UBC in 1952, again taking six courses per term. During summers, he continued working as a fisherman to assist his father, which he did until 1957.

In 1955, he graduated from UBC and, on a friend’s suggestion, applied to medical school. “To my surprise, I was accepted,” he smiled. During medical school, he faced a life-threatening subphrenic abscess. Thanks to the intervention of a university medical professor, his life was saved, but he lost a year of studies. Undeterred, he graduated in 1960.

Two weeks later, he married, and the couple embarked on a honeymoon road trip across northern United States in a Volkswagen, heading to Toronto. There, he completed a one-year internship at Toronto Western Hospital.

A First-Generation Japanese Canadian’s Story

Before the internment, Vancouver was home to a vibrant Japanese community. As the eldest son, Dr. Horii admits he was sometimes spoiled. He fondly remembers visiting a small confectionery shop on Powell Street near the Vancouver Buddhist Temple. “I used to get anpan (sweet red bean buns) there,” he said. “The shop was run by a couple named Matsumoto.” The Horii family grew close to the Matsumotos, but they lost contact after the internment began.

In 1961, when he began practicing as a doctor, the Matsumotos became his patients. It was then he learned that Mr. Matsumoto had been a Canadian war veteran in World War I. “I saw a photograph of him in uniform—tall, handsome, and strong,” he explained. “His name was Kingo Matsumoto.”

During World War I, 222 Japanese Canadians served in the Canadian military despite facing severe discrimination in British Columbia. Many had to travel to Alberta to enlist, as they were barred from joining in BC. Of those who served, 54 lost their lives. A memorial for these fallen soldiers, built by the Japanese Canadian community, now stands in Vancouver’s Stanley Park.

Japanese Canadians who served in World War I were eventually granted Canadian citizenship. “At first, the Canadian government refused, but in 1931, they relented. It was the first time citizenship was granted to people of Asian descent,” he explained. However, this recognition was short-lived. “When war with Japan broke out in December 1941, Mr. Matsumoto was labelled an ‘enemy alien,’ stripped of his citizenship, and interned,” he added.

Like other Japanese Canadian veterans of World War I, Mr. Matsumoto endured unjust treatment. Having inhaled poison gas while fighting in Europe, he suffered from lung disease. “It’s ironic, isn’t it?” Dr. Horii said, reflecting on the bitter irony on how the Canadian government treated men who risked their lives for this country with such cold disregard.

On Japanese Canadian Internment and Discrimination

“More towards the end of my working career, I got interested in talking about the internment and racism,” said Dr. Horii. Known professionally as Dr. Aki Horii, he built a reputation as a physician fluent in Japanese, caring for many first-generation Japanese Canadian patients. Now, he speaks to elementary and high schools, universities, and colleges, sharing his experiences and shedding light on the realities of discrimination.

Mr. Horii explains that the Canadian government’s discriminatory actions against Japanese Canadians were fueled by the prejudiced statements and attitudes of politicians. Discrimination was openly endorsed by members of the federal government, the BC provincial government, and Vancouver city officials, with federal MPs wielding significant influence.

To illustrate the depth of prejudice, he cites discriminatory remarks made by politicians and published in the Vancouver Sun:

“Japs must never be allowed to return to British Columbia.”

“The government’s plan is to get these people (Japanese Canadians) out of BC as quickly as possible. I will spend every remaining moment as a public official ensuring this happens, so they will never come back here.”

“Not a single Jap should be allowed between the Rockies and the Pacific.”

Dr. Horii also references a 2015 Vancouver Sun article that examined the events of 1942. The article explained how the attack on Pearl Harbor was used as a pretext to forcibly remove Japanese Canadians from the BC coast. For decades, BC had opposed immigrants from Asia, but federal government had resisted taking sweeping measures. However, under the guise of wartime necessity, Japanese Canadians were forcibly relocated inland. The article highlighted that the war provided a convenient opportunity to resolve a long-standing “problem.”

“That tells you all that saying the editorial that they used the military, the war Japan, as an excuse to get rid of all the Japanese Canadians from the province of British Columbia,” Dr. Horii stated emphatically. The mistreatment continued even after the war ended on August 15, 1945. That year, the Canadian government gave Japanese Canadians living in BC an ultimatum: relocate east of the Rockies or face deportation to Japan. Approximately 4,000 chose deportation, while many others moved to Alberta or Saskatchewan.

Dr. Horii underscores that discrimination can occur anytime and anywhere, leaving deep and lasting scars. He shares a personal story: “At a doctors’ meeting, one physician repeatedly used the term ‘Jap’ during the conversation. I couldn’t sleep for a month afterward.” At the next meeting, he confronted the doctor, who apologized.

“Discrimination often arises in the most unexpected places,” he reflected quietly. “This is what I tell students when I share my story.”

(Text: Naomi Mishima)

Related Articles

***

***