“Valuing the Japanese Canadian Community”

Ms. Kikuko Tasaka

Born in 1939, Steveston, British Columbia

Moved to Greenwood in 1942, back to Vancouver in 1958

Paternal grandfather originally from Ehime Prefecture, maternal grandfather originally from Mio, Wakayama Prefecture

Life in Greenwood

The Tasaka family relocated from Steveston to Greenwood in 1942. Before the internment, Ms. Tasaka’s father was a barber in Steveston. “We had a big and nice building, but we were relocated shortly after it was built,” she said. Ms. Tasaka was three years old at the time.

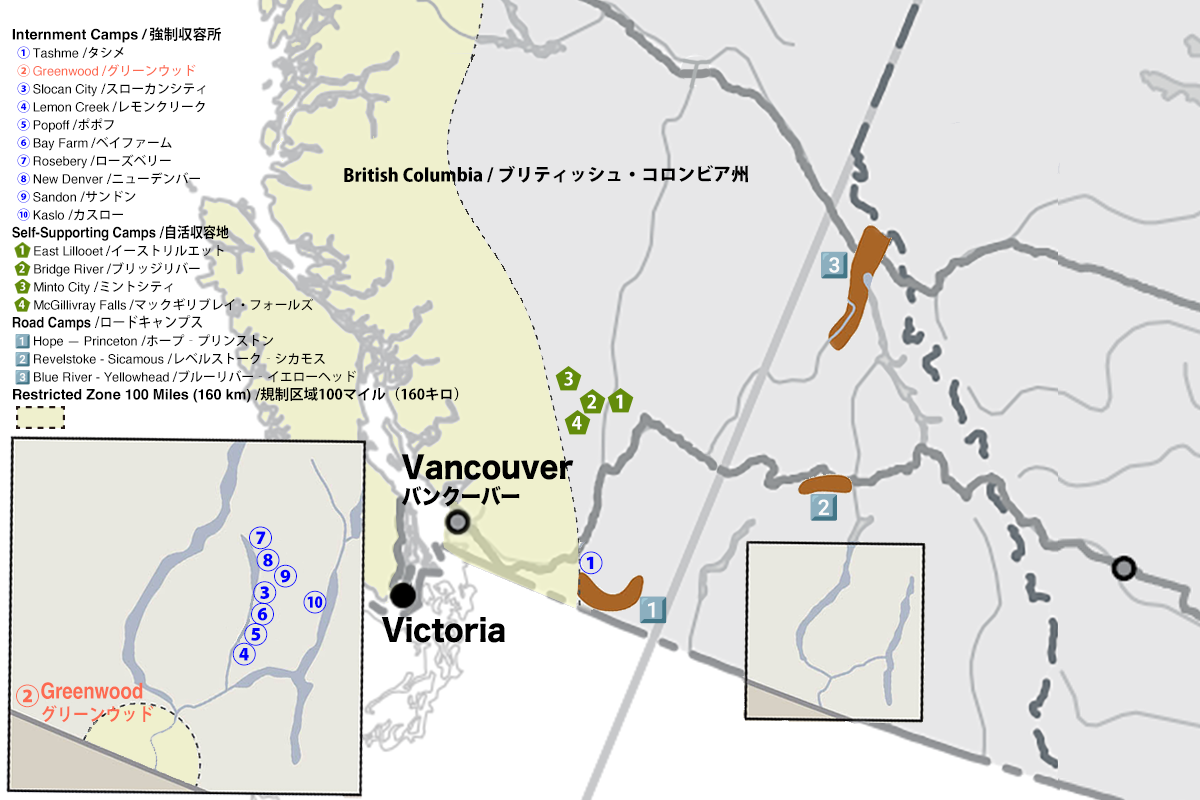

Greenwood, located in the central-southern part of British Columbia, near the American border, and about 400 kilometres east of Vancouver, was one of the government-supported internment sites. Unlike other camps, Greenwood welcomed Japanese Canadians who were forcibly relocated from Vancouver. Franciscan Friar Benedict Quigley and Franciscan Sisters played significant roles in supporting the Japanese Canadian community there.

“I didn’t have any bad experiences at all in Greenwood,” Ms. Tasaka recalled. She noted that carpenters arrived in Greenwood ahead of the internees to build essential items like beds, tables, chairs, and even Japanese-style baths to prepare for their arrival.

However, there were challenges. “The place was cold in winter in the first year because Vancouver was warm. Greenwood was deep in the mountains, so it was really cold,” she remembered. To cope, they used discarded military blankets and uniforms they purchased. “That’s how we managed because we had nothing.”

Despite the initial hardships, Ms. Tasaka found life in Greenwood enjoyable. School began promptly, run by Franciscan nuns. “That school was very good. It went up to Grade 8, and they even taught us skills like typing for jobs,” she said.

The community also organized Japanese festivals. “People wore kimonos, and there was dancing. The Japanese Canadian community also put on plays, and it was really fun,” she added. They formed a strong community because the town accepted Japanese Canadians. “The hakujin (white) residents of Greenwood were happy to have Japanese Canadian people come. They were pleased because the Japanese shared their culture, taught various things, and organized festivals. Everyone was glad.”

Even after the internment ended, Ms. Tasaka’s parents chose not to leave Greenwood. “They were happy, saying there was no town as good as Greenwood,” she said.

Overcoming Discrimination in Vancouver

After living in Greenwood for about 15 years, Ms. Tasaka returned to Vancouver. She recalls that many people left Greenwood around the age of 18 to look for work. “There were no jobs in Greenwood,” she explained. She was one of them.

By then, it was the late 1950s. Although the internment officially ended in 1949 and Japanese Canadians were free to move as they pleased, Ms. Tasaka says she will never forget the discrimination she faced upon returning to Vancouver. “The people here looked down on us. Not everyone—there were good people, too—but we all had to endure it. We had no choice but to endure it. The discrimination was really tough. It was painful to feel discriminated against. Some people were terrible, but there was nothing we could do.”

She believes the widespread discrimination contributed to why many Nisei (second-generation Japanese Canadians) stopped using the Japanese language. “When everyone came back to Vancouver, they didn’t want to speak Japanese. They tried to use English as much as possible,” she said. “Because of the discrimination, they didn’t want to show they were Japanese. At the time, we had no choice.” Now, when she speaks with other Nisei, she senses some regret in their voices as they say, “I wish I had kept speaking Japanese.”

As Sansei (third-generation Japanese Canadian), Ms. Tasaka speaks fluent Japanese. She attributes this to her upbringing in Greenwood, where they spoke Japanese at home and within the community. “Our parents couldn’t speak English, so we used Japanese,” she adds. In Greenwood’s large Japanese Canadian community, she didn’t feel discrimination there. “But when we returned to Vancouver, society was different, and we couldn’t use Japanese.”

Despite the challenges, she and her peers formed their own community in Vancouver. They gathered occasionally and enjoyed dance parties and festivals. “It wasn’t so bad, despite the discrimination,” she said. “We endured and did our best.” She added that they are still friends after 60 years.

Valuing the Japanese Canadian Community

“I still think of myself as Japanese, no matter where I am—even though I’m already a third-generation Japanese Canadian,” Ms. Tasaka said. Her paternal grandfather immigrated from Ehime Prefecture in 1890. He ran a business on Salt Springs Island, near the southern part of Vancouver Island. Her father was born there. Her maternal grandfather came from Mio, a village in Wakayama Prefecture. “Our parents passed us so many good aspects of Japanese culture. I never want to lose that.”

Ms. Tasaka, who often interacts with people visiting from Japan, shared, “I don’t know how to put it…in English, I’d say they are ‘kind’ and ‘considerate.’” Although she was born and raised in Canada and engages with other Canadians, she admitted, “I don’t know why, but I feel more comfortable with Japanese people. Maybe I shouldn’t say that, but it’s true,” she added with a laugh.

She volunteers at the Tonari Gumi, a Japanese-language volunteer organization founded in the 1970s to help issei (first-generation) and nisei seniors who struggled with English. Today, Tonari Gumi continues to provide Japanese-language services, mainly for seniors.

“I wanted to do today’s interview in Japanese,” she said. One reason is to inspire the Nisei, who often lack confidence in speaking Japanese. Another reason is to share the experiences of the Issei and Nisei, who endured hardship during the internment, directly with people from Japan who may be unfamiliar with their stories.

“Sometimes, people don’t understand the struggles (the) Issei and Nisei faced. I want immigrants from Japan to know what the Issei went through,” she explained. She hopes people in Japan take note and learn what happened to Japanese Canadians during and after the war.

(Text: Naomi Mishima)

Related Articles

- History of the Japanese Canadian Community

- Japanese Canadian Internment (Chronology)

- Greenwood and Grand Forks: “Japanese Canadian Stories”

***

***