On May 5, the British Columbia government announced that the Japanese Canadian community would receive two million dollars for the well-being of Japanese Canadian internment surviving seniors.

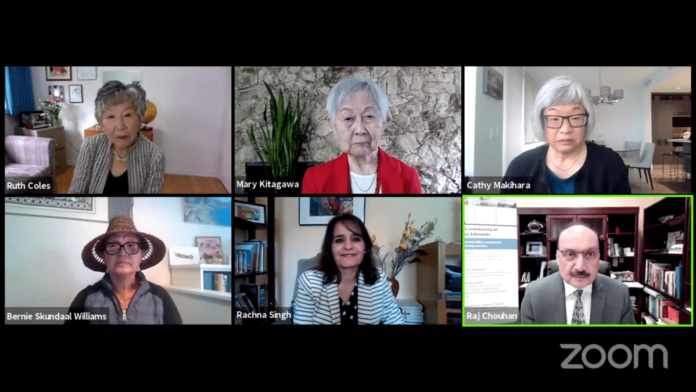

In the press conference, Ms. Rachna Singh, Parliamentary Secretary for Anti-Racism Initiatives, said, “we need to acknowledge the province’s historical wrong, and we need to honour the survivors, and we need to provide lasting recognition of these traumatic events.”

Funding will be provided to the Nikkei Seniors Health Care and Housing Society (NSHCHS) who will develop and deliver health- and wellness-oriented programming for Japanese Canadian internment survivors.

“Funding will directly support survivors and those most impacted by these injustices 80 years ago,” said Ms. Singh. “Nikkei senior society will be working with the National Association of Japanese Canadians to ensure this funding goes to other organizations that serve survivors.”

The National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC) has been working with the province for years. Ms. Singh thanked the association for their recommendations and gave particular thanks to Ms. Suzanne Tabata of NAJC for her support.

The government, however, said this is just the beginning. “This initial grant is the first step toward lasting recognition of the trauma suffered by the community. We are committed to working with the National Association of Japanese Canadians over the coming year to define recognition opportunities in 2022 and beyond,” said Ms. Singh. She reiterated that there is more to do to meaningfully acknowledge these historical injustices by the B.C. government and deliver a lasting legacy for the Japanese Canadian community.

Ms. Ruth Coles, president of the Nikkei Seniors Health Care and Housing Society, a second generation of Japanese Canadian, and an internment survivor, said in the press conference that “this fund will definitely meet some of the health and wellness needs of Japanese Canadian senior survivors. The seniors have unique needs that stem from their lived experience of internment, forced uprooting, dispossession and displacement, which caused many to relocate outside of British Columbia.”

The Canadian government forcefully moved almost 22,000 Japanese Canadians 100 miles away from the B.C coast between 1942 and 1949, simply because they were Japanese descendants, despite many were Canadian citizens born in Canada. Many were interned and forced to live in harsh living conditions.

“These actions led to challenges that have followed the seniors throughout their lives, their education was disrupted, friendship and trust have taken away. And for many, it could experience of economic hardship, health issues and shame with little resolution for these actions,” said Ms. Coles. This fund will also “provide community asset mapping to identify healthcare gaps and this data will be used for future projects.”

Ms. Cathy Makihara, former executive director of the Nikkei Seniors Health Care and Housing Society, revealed a few details of how they would use this fund. This Japanese Canadian survivor’s health and wellness fund will directly benefit the surviving seniors’ support programs, education equipment, and activities to improve the quality of life in the health and wellness of the survivors. She also said that “the survivors are today well into their 80s and 90s and older. And bearing this in mind, we will be moving quickly.”

They plan to set a dedicated website for the Japanese Canadian survivors’ health and wellness fund currently in development. “The goal is to have these funds available as grants and accepting applications in the near future, and the project will be concluding in spring 2022.”

This fund also covers not only survivors in B.C. but throughout Canada. Ms. Makihara noted, “what we intend to do is go to different communities. We’ll be beginning outreach all across Canada to identify what their priority needs are. And there will be grants going across the country as to what the criteria will be.” She continued to say, “there are some areas that will be very underserved, and there are no supports for these seniors from the community.” More details will be revealed soon.

Internment survivors need more opportunities to tell their stories

As Ms. Makihara said, all of the survivors are now in their 80s and 90s, which means only a few seniors can still tell their experiences. In the press conference, one of the surviving seniors told her story. Ms. Mary Keiko Murakami Kitagawa was seven years old when she was forcefully removed from Vancouver with her family.

She introduced herself as ‘one of the survivors of Canada’s approving dispersal disposition and enslavement, imprisonment, and deportation of Canadians of Japanese descent.’ Many interment survivors do not willingly talk about what happened because raising their voices is not appropriate for the Japanese culture, but partly because speaking of it will deepen their wounds. It takes courage for any victims to speak up about what happened. And Ms. Kitagawa has often courageously speaken up about her experiences as opportunities allowed her. In the press conference, she did it again.

“The event was euphemistically called internment, but I will call it incarceration, a more applicable word to describe our imprisonment. Many euphemisms were used by the government to give a false impression of what was done to 22,000 loyal, hard-working Canadians,” she said. “When talking about our incarceration, the stress is put on the loss of material things such as land, homes, boats, businesses and personal belongings. These were what the Japanese Canadians acquired by hard work and sacrifices.”

Until the internment was forced, even if it was a difficult time for Japanese Canadians, they found ways to make themselves happy in Vancouver. People were helping each other in the community. They had dreams for their future. “My young parents lost the most productive years of their lives. Everyone lost their dreams of what they had planned. They lost their communities, their friends, their education, their ability to pass on intergenerational wealth, their language opportunities, their hopes and plans for the future. Many elderly people died from causes forced upon them.”

There are things you can never regain. The Japanese Canadian community had lost so much and has never been the same again ever. “The elderly survivors who are living now were children who must now carry on pain of that cruel journey that our parents and grandparents suffered and were forced to take. Their journey of humiliation, betrayal, alienation, and denial of basic right must not be forgotten.”

In the opening remarks of the press conference, Ms. Burnie Skundaal Williams said, “We share a parallel history with the Japanese Canadians as a First Nations person.” She was a residential school survivor, an Indian day school survivor, and a resident of the downtown eastside. “I’ve learned about the history of the Japanese Canadians in my community and the neighbourhood where many thousand were forced from their homes with the promise of a return which never happened; instead land and belongings were pillaged, sounds very familiar as a First Nations person.”

She praised the community’s effort to say, “it is sometimes hard to move on, but they did.” Still, she continued, “I have seen the scars, and I’ve seen the resilience in my community.”

The scars will never go away for a person and the community, no matter how successful the Japanese Canadians were. How can we ease their pains? Ms. Williams gave a hint. “We share the common goal is to educate about this history.”

Now more than ever, it is crucial for the internment surviving seniors to tell their experiences, anger, sorrows and hopes to let us educate. And hopefully, the talk will ease some of their pains before it’s too late.

(Text: Naomi Mishima)

Related articles