はじめに

日加関係を応援頂いている皆さま、音楽ファンの皆さま、こんにちは。

4月の声を聞くと春の訪れをイメージしますが、今年のオタワは違います。温暖化の時代とは思えず、4月になっても真冬に逆戻りする日もあります。さすが、世界で最も寒い首都の一つです。とは言え、街を覆っていた雪も徐々に溶け出し、樹木も目を凝らして見れば蕾が膨らみ始めています。厳しい冬の後の春は喜びもひとしおです。

さて、今回の「音楽の楽園」は、カナダが生んだ現代音楽の鬼才クロード・ヴィヴィエです。移民立国のカナダを体現するモントリオール出身。出生の瞬間から旅路の終焉まで正に波瀾万丈そのもの。「事実は小説より奇なり」を体現したような人生を生きました。アンブローズ・ピアスの『悪魔の辞典』が芸術家について「法律を巧みにかいくぐる術に長けた者」と定義していたことを思い出します。

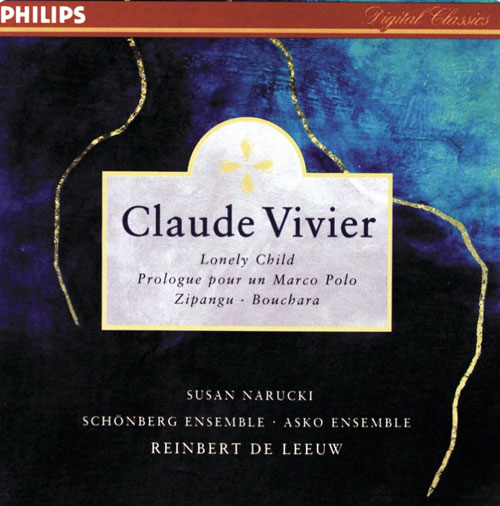

クロード・ヴィヴィエは、弱冠34歳で夭折した天才。現代音楽の巨匠カールハインツ・シュトックハウゼンの下で学びましたが、師の作曲技法を消化・吸収し、誰にも似ていない唯一無二の個性を確率しました。日本にも短期間滞在し、東洋的な要素を絶妙に取り入れているのもヴィヴィエの真骨頂です。短期間に本格的な作品を40以上残しています。どれも時代の先を行く真の前衛。没後、急速に評価が高まりました。代表作は、「ソプラノと管弦楽のための《みなし児(Lonely Child)》」です。現代と伝統、東洋と西洋が交差する音楽の斬新な響きに満ちています。今なお、美しく刺激的です。

それでは、クロード・ヴィヴィエの辿った音楽的冒険を追体験しましょう。

1948年4月14日〜モントリオール

クロード・ヴィヴィエは、1948年4月14日、モントリオールに誕生したと記録されています。但し、両親については姓名・人種等一切不明です。と言うのも、誕生直後にカトリック教会が運営する孤児院に置き去りにされたからです。その段階では、名も無き赤ん坊でした。教会により、クロード・ロジェと名付けられ、孤児院で養育されます。そして、2歳半の時に、詳しい経緯は分かりませんが、モン・ロワイヤル公園の側のマイルエンド地区の労働者階級のヴィヴィエ家に養子として引き取ら、クロード・ヴィヴィエとなりました。

すくすく成長すると期待されていたものの、言葉を話さなかったため特別養護施設への通院も一時は検討されたようですが、6歳になる頃、話し始め健常者だと判明し、養父母はほっとしました。ところが、それも束の間、クロードが8歳になる頃、同居していた養父母の伯父から性的虐待を受けていたことが発覚します。教会の懺悔で、クロードが告白したからです。しかし、養父母は、クロードが嘘をついていると激怒したと言われています。

この一件以来、家族関係がギクシャクし始めたと云います。同時に、クロードの自我が芽生え、人格が形成されていくのです。

思春期

1961年、13歳になったクロードは、1817年に創設された名門のカトリック寄宿神学校、マリスト・ブラザーズ校に入学します。ここは、基本的には聖職者養成機関で、質の高い教育で知られていました。クロードは全ての科目で非常に優秀な成績を残します。中でも特に文学と言語学そして歴史に強い関心を示します。アルチュール・ランボーの詩に感銘を受け、ラテン語やギリシャ語も勉強しました。また、ドイツ史に強く惹かれ、ドイツ語も堪能でした。この頃、クロードは友人に、自分の両親はドイツ或いは東欧出身のユダヤ系で音楽家だ、と話しています。如何なる根拠があったのか分かりませんが、後年ドイツへ留学していることを思うと、血脈の影響があることを感じさせます。

また、マリスト・ブラザーズ校在学中に、クロードは自分が同性愛者であることに気付きます。1960年代のカナダでは、今と全く状況が異なっていて、同性愛はカナダ刑法に云う「重大な不品行為」として処罰の対象でしたし、社会的にも同性愛への偏見は根強かったのです(この状況が変わるのは、ピエール・トルドー首相の登場を待たねばなりません)。それでも、モントリオールは、カナダの中では突出して文化的に多様でゲイ・サブカルチャーが存在していたと言われています。秘密裏に運営されるゲイ・バーやサロンもあったそうです。とは言え、10代のクロードが性的指向を表現するのは極めて困難な社会状況だったのは間違いありません。そんな孤独や葛藤や渇望が音楽を求める本能と化学反応を起こしたのかもしれません。因みに、クロードは18歳の時に、自分が同性愛者であることを告白しています。

音楽への目覚め

そこで、クロード・ヴィヴィエの音楽についてです。彼の音楽的原点は教会でした。養父母に連れられて参加した礼拝で聴いた聖歌隊の合唱は、声と歌への憧憬を深めます。パイプオルガンの荘厳な響きが幼きクロードの中枢に深く刻み込まれたのです。特に、クロード10歳の時、1958年12月24日のクリスマス・イブの深夜ミサで聴いた聖歌が決定的で、「その瞬間に何かが自分の中で開かれた」と後年語っています。

上述のとおり、ヴィヴィエ家の家庭環境は決して望ましいものとは言い難かった訳ですが、クロードは音楽への強烈な関心と非凡な才を垣間見せます。養父母は、クロードのためにアップライト・ピアノを買い、時折ピアノ・レッスンにも通わせました。

マリスト・ブラザーズ校は、カトリック教義を核にしていましたから、ミサ、晩課、グレゴリオ聖歌が日常的に演奏される環境でした。音楽は宗教的実践の不可分の一体だったのです。一方、教育カリキュラムとしての音楽教育は限られていました。そんな中、クロードは、ほぼ独学で音楽について学びます。特に、モーツァルト、チャイコフスキー、バルトーク、シェーンベルグの音楽に魅了されました。作曲も始め、仲間に聞かせていたと言います。また、地元のバレエ教室でピアノの伴奏をしたり、音楽を教えたりしました。また、パイプオルガンの音色に魅せられ、パイプオルガンが設置されている地元の教会を訪れては、ミサの伴奏をさせてもらうようになったといいます。

マリスト・ブラザーズ校は聖職者養成学校だったにもかかわらず、クロードは音楽にのめり込みます。同時に、クロードの性的志向はカトリックの寄宿舎学校では全く容認されませんでした。結局、放校処分を受けました。クロードは、音楽への道を模索します。生活費を稼ぐために、地元のレストラン等でアルバイトをしたそうです。

モントリオール音楽院

1967年秋、クロード・ヴィヴィエは、晴れて名門モントリオール音楽院に進学します。専攻は、ピアノと作曲です。作曲は、フランス現代音楽の巨匠オリビエ・メシアンの高弟ジャイルズ・トレンブレイ教授に師事します。トレンブレイ教授は、作曲には無限の可能性があり、特定の時代の技法ではなく全方位的に学ぶべきとの信念を持っていました。ヴィヴィエは、グレゴリア聖歌、バッハからアルバン・ベルグまで500年を優に超える時間軸で音楽の真髄に迫り学びます。ヴィヴィエは、授業の後も廊下でトレンブレイ教授を質問責めにしたとの逸話が残っています。ヴィヴィエの関心の核心は、旋律を如何に活かすかだったと言います。ハーモニーとリズムと音色を駆使し、誰も到達したことのない境地に音楽を導くのがヴィヴィエの野望だったのでしょう。

この頃、ヴィヴィエが音楽を学んだのは音楽院の閉じた空間だけではありませんでした。自由な気風に溢れるモントリオールでは、世界最先端の音楽を紹介するコンサートも頻繁に開かれていました。そして、ヴィヴィエは生まれて初めてシュトックハウゼンの前衛音楽に触れ、衝撃を受けます。1968年のことでした。

音楽院の内外から刺激が、ヴィヴィエの創造中枢の爆発への導火線を発火させます。ヴィヴィエの最初期の本格的な作品「ソプラノ、クラリネットと打楽器のための《オジカワ》」も発表されます。20歳の自画像と言ってよいでしょう。大いなる可能性を感じさせます。トレンブレイ教授は、ヴィヴィエの良き理解者でした。巨大な才能の原石の発見者にして親友となりました。教授の強力な推薦もあって、ヴィヴィエは、カナダ芸術評議会から奨学金を得ます。そして、欧州へと飛び立ったのです。この時、23歳です。

ヨーロッパにて

1971年から73年まで3年間、クロード・ヴィヴィエはクラシック音楽の本場たる欧州に留学します。疾風怒濤の1960年代を経て、欧州は大きな変革の真っ只中にありました。グレゴリア聖歌、ジョスカン・デ=プレ、ヴィヴァルディ、バッハ、ヘンデル、モーツァルト等々、古典音楽を育んできた欧州は、今や全く新しい革命的な音楽の揺籃の地です。ヴィヴィエは、現代音楽を牽引する3人に師事します。

まず、国立パリ高等音楽院で指揮者・作曲家のポール・メファノに師事します。特に、詩・言葉と音楽の深淵な繋がりを探求しました。次にユトレヒトにあるハーグ王立音楽院付属ソノロジー研究所でゴッドフリード・マイケル・コーニングに師事します。この研究所は、最先端の電子音楽を主導していました。最新技術と音楽の関わりを体得する絶好の場でした。

最後に、ケルン音楽院です。ここでは、20歳のヴィヴィエに強烈な霊感を与えた稀代の作曲家シュトックハウゼンが教鞭を取っていたのです。彼にとっての欧州留学の核心です。希望に胸を膨らませるヴィヴィエでした。しかし、シュトックハウゼンは、課題に対しヴィヴィエが書いた楽曲を評価せず、弟子入りを断ったと言います。ショックを受けるヴィヴィエですが簡単には諦めません。最終的には、受け入れられ、1972年から2年間、ここで、シュトックハウゼンの音楽・美学・思想を徹底的に学んだといいます。作曲技法だけではなく、音楽に直結する時間と空間と音響の関係性、更には曲づくりの背景と骨格をつくる思想です。ヴィヴィエにとっては、誰の真似でもない自らの音楽世界を構築する上で極めて重要な土台となるのです。一方、シュトックハウゼン教授はと言えば、ヴィヴィエに関して好意的コメントすることはなく、評価は総じて高くはなかったそうです。師弟関係は、決して一筋縄ではいかないという事でしょうか。

モントリオールの新進気鋭

1974年、3年間に及んだパリ、ユトレヒト、ケルンでの実り多き留学を終えて、ヴィヴィエはモントリオールに帰還します。作曲家としての内実は充実しましたが、一般には無名です。市内のアパートの賃料も安くはありません。地元の音楽学校で教師をして生活費を稼ぎながら、新進気鋭の作曲家としての道を歩み始めます。

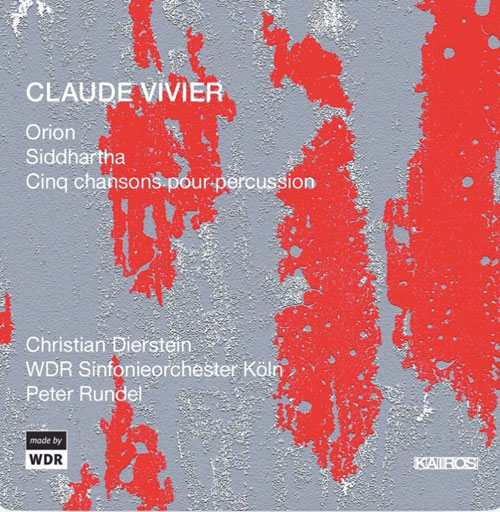

やがて、大きな転機が訪れます。CBCがヴィヴィエにカナダ国立青少年管弦楽団のための新曲の作曲を委嘱して来たのです。結果、生み出されたのが、代表作の一つ「シッダールタ」です。シッダールタは仏陀のことで、ヘルマン・ヘッセの小説『シッダールタ』にインスパイアされたものです。真理を探求し精神的覚醒に至る旅路を描いた物語に呼応するような楽曲です。ヴィヴィエ自身は「自分自身の声を見出そうとした時期」の作品だと述べています。シュトックハウゼンの重力圏から離れ、ヴィヴィエ流の音楽美学を確立する記念碑作品と評されています。実は、生前は演奏される機会はなく、没後9年を経た1992年にケント・ナガノがモントリオール交響楽団を指揮して初演しました。様々な打楽器を活用し変幻自在なリズムと多彩な音色が観客を魅了し、圧倒的な成功でした。

中東アジア紀行

ヴィヴィエは、1976年から77年にかけて、エジプト、日本、イラン、タイ、シンガポール、バリを訪れています。欧州とは全く異なった文化的・歴史的な空間に身を置いたのです。それぞれの国で独自に発展して来た音楽について学び、吸収し、それをヴィヴィエ的な作曲語法の中に昇華させていきます。バリではガムラン音楽の影響を受けました。

日本では、雅楽、仏教音楽、能、声明、歌舞伎等に触れています。間を大切にする独特のリズムの感覚や和楽器的な音色が代表作「ジパング」に滲んでいます。CDも出ていますし、YouTubeでも聴けます。現代音楽は苦手という方も、聴けば、東洋の響きの中に潜む音楽の驚きと喜びを感じられると思います。

パリ〜最終章

1982年6月、クロード・ヴィヴィエは、パリに移住します。カナダ芸術評議会の奨学金を得て更なる音楽の高みを目指したのです。ヴィヴィエにしてみれば、現代音楽作曲家としてカナダで出来ることはやり尽くしたとの実感があったと言います。

パリでは、基本的に創作活動に没頭していました。特に、チャイコフスキーの死を題材とした新作オペラに情熱を傾け、構想を練っていました。また、「魂の不滅を信じるか?」と題する新曲の作曲を始めていました。同時に、パリ高等音楽院関係者との交流もあり、正式な教授ではなかったものの、ケベックの音楽事情等についてアドホックに講義をしていたようです。

一方、私生活は奔放で、頻繁にゲイ・バーを訪れていたことが知られています。夜な夜な行きずりの関係に溺れていたとも言われています。1983年1月には、そんな相手から暴行を受ける事件が起きます。友人たちは心配し、真剣に助言した訳ですが、ヴィヴィエの私生活は変わることはありませんでした。

それでも、作曲家としては希望に満ちた将来が待っていたはずです。しかし、クロード・ヴィヴィエの生涯は、1983年3月7日、突然、終わります。パリの自宅アパートにて、その夜ベルビル地区のバーで出会った男娼に刺殺されたのです。嗚呼!

葬儀は3月3日、パリのペール・ラシェーズ火葬場で行われました。そして、4月14日(ヴィヴィエの35回目の誕生日)、モントリオールの聖アルバート・ル=グラン教会において追悼式が行われています。

結語

クロード・ヴィヴィエは、34年と11か月の人生航路をドラマチックに展開し生涯を終えました。彼の肉体が滅んで早くも42年が経ちます。一方、彼が残した音楽は時間の経過を経て輝きを増しています。

(了)

山野内勘二・在カナダ日本国大使館特命全権大使が届ける、カナダ音楽の連載コラム「音楽の楽園~もう一つのカナダ」は、第1回から以下よりご覧いただけます。

「音楽の楽園~もう一つのカナダ」

山野内勘二(やまのうち・かんじ)

2022年5月より第31代在カナダ日本国大使館特命全権大使

1984年外務省入省、総理大臣秘書官、在アメリカ合衆国日本国大使館公使、外務省経済局長、在ニューヨーク日本国総領事館総領事・大使などを歴任。1958年4月8日生まれ、長崎県出身