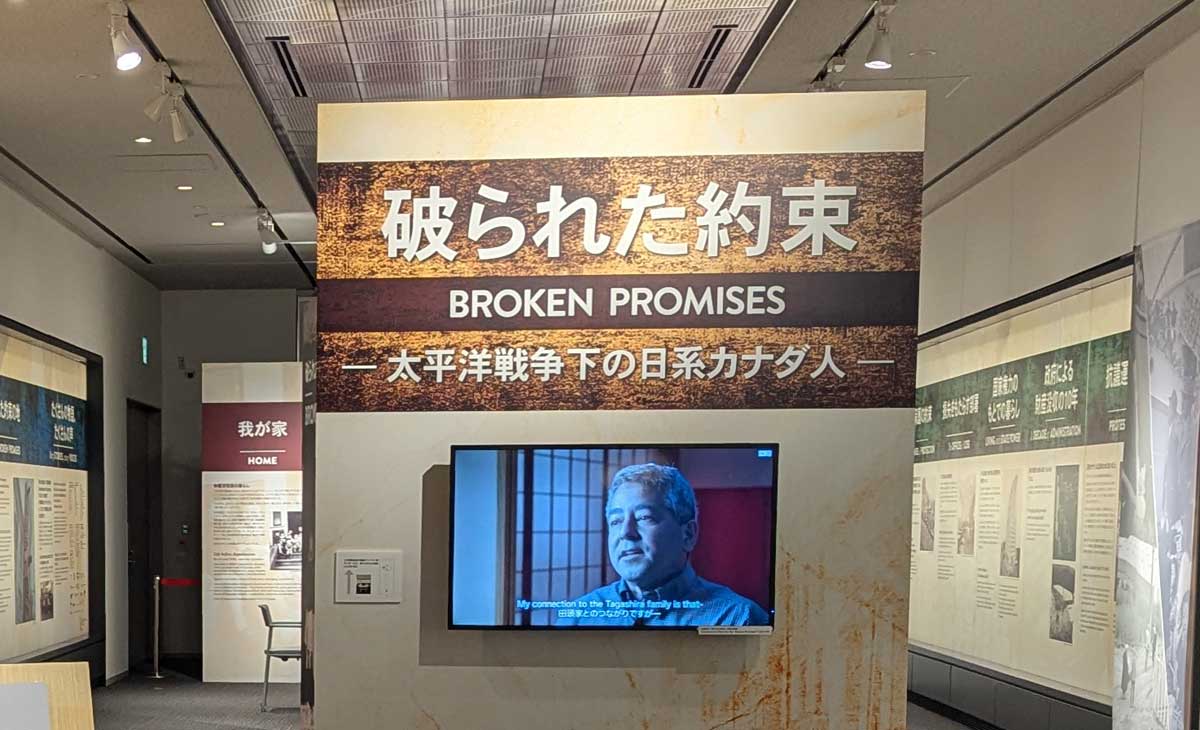

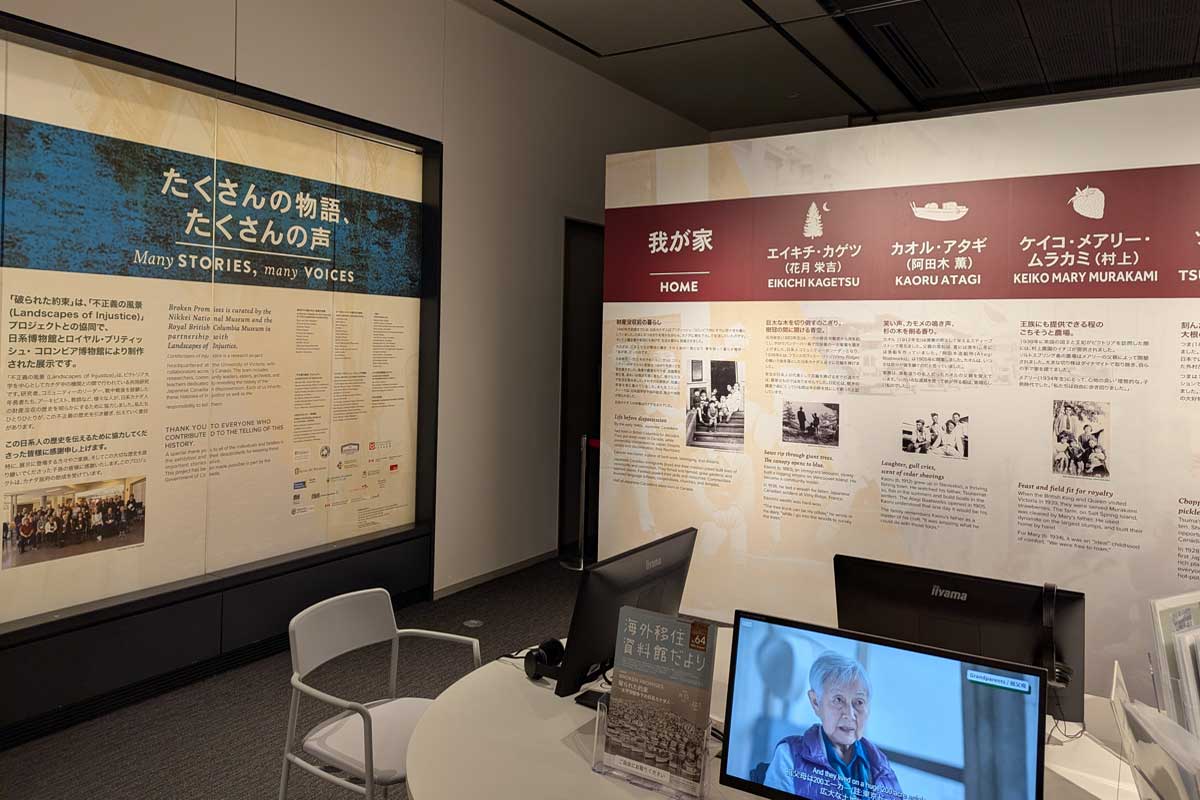

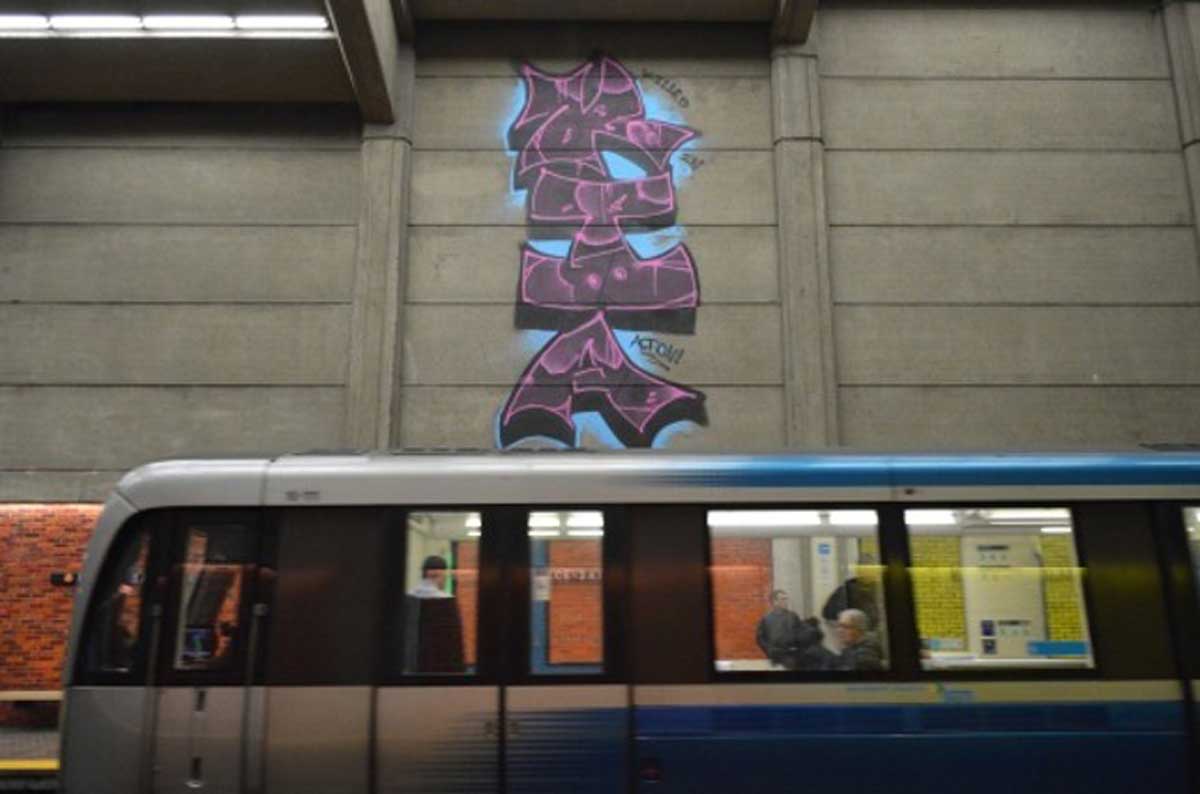

「Broken Promises 破られた約束」展示会場入り口。2025年10月2日、横浜市。撮影 三島直美

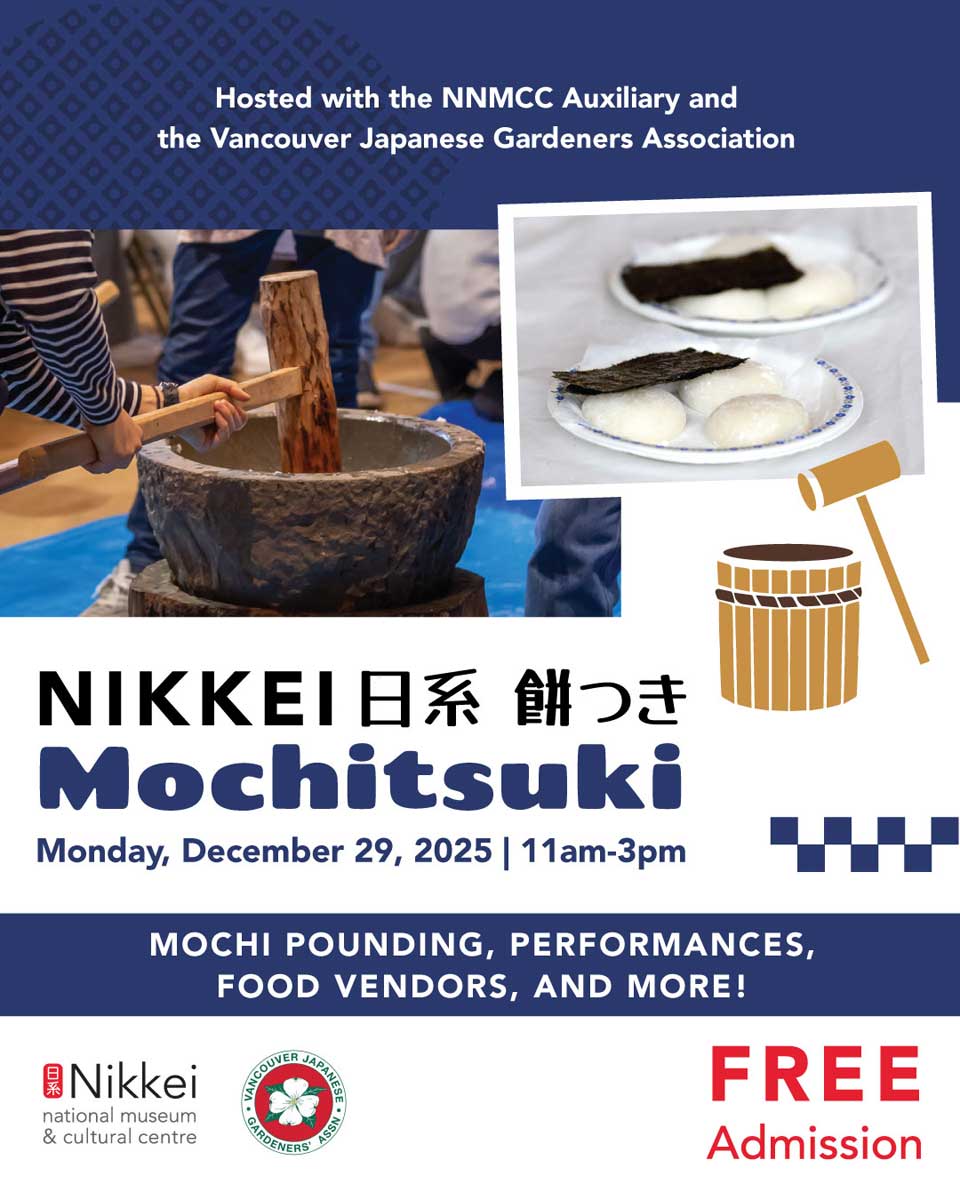

神奈川県横浜市にあるJICA横浜海外移住資料館で企画展示「Broken Promises 破られた約束-太平洋戦争下の日系カナダ人-」(12月7日まで)が開催され、オンラインではバーチャル展示(2026年3月31日まで)が閲覧できる。

同資料館ではカナダをテーマにした企画展は2015年「Taiken体験-日系カナダ人 未来へつなぐ道のり―」に続いて2回目という。

今年10月、同資料館で話を聞いた。

企画展について 今回の企画展は学芸担当の小嶋茂さんが「Landscapes of Injustice」のプロジェクトメンバーだったことから依頼を受け実現したという。

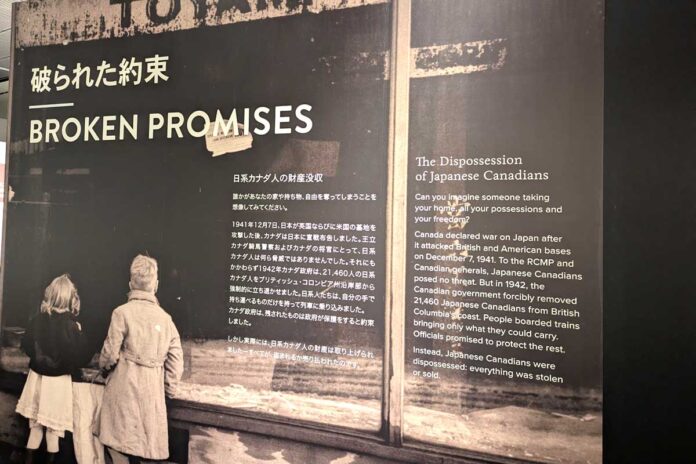

日系文化センター・博物館は「Broken Promises」の展示について、「7年間にわたる学術研究および複数の機関とコミュニティが関与した」研究プロジェクト「Landscapes of Injustice」で明らかになった、カナダ政府による日系カナダ人強制収容政策で没収された財産の全記録「敵性財産資産管理局」関連の情報を基に、強制収容経験者やその家族などの証言などを含めて制作と説明。2020年9月から21年6月27日まで同センター内「カラサワミュージアム」で展示された。

それを「Broken Promises 破られた約束」日本巡回展示実行委員会が日本向けに編集してカナダ移民に関係が深い関西圏を中心に巡回展示している。資料館の展示では、さらにカナダへの日本人移民の歴史を知らない人でも理解できるようにと移民の歴史から説明したという。同資料館学芸員の原本義浩さんは「カナダへの移民というところから歴史を語らないと強制収容から財産没収、リドレスまでたどり着けないと感じました」と振り返る。

カナダへの移民の歴史を紹介するパネル。2025年10月2日、横浜市。撮影 三島直美

膨大な英語の資料を参考にして11枚のパネルにまとめた。そこにはカナダへの移民の始まりから、日系人への差別、真珠湾攻撃を機に始まったカナダ政府の日系人強制収容と財産没収、終戦後も続いた強制移動政策、そしてリドレス運動などを紹介している。移民がいつ始まって、なぜブリティッシュ・コロンビア州南西部に超局所的に生活していたのか、それに対してそこにいたカナダ人の感情はどうだったか、第2次世界大戦で同じくカナダと戦ったドイツ系やイタリア系はどのような扱いを受けたのか、そこまで紹介しないと事実の裏にある全体像が見えてこないと話す。「ただ単に、カナダ政府がひどいことをしました、日系カナダ人がひどい目に遭いました、という展示で終わりたくないと思っていました」。

心がけたのは、「(Landscapes of Justice)プロジェクトが目指していたものをきちんと勉強して、なるべくそれに沿った形で日本語に訳して提供すること」。資料館での展示に当たっては日系文化センター・博物館のシェリー・カジワラ館長と親切なボランティアスタッフの助けを借りて「可能な限り事実に即したものを作ろうと思ったんです」。ただ展示準備中にバンクーバーに行く機会はなく、「カナダに漂う『公正』の概念の空気感が想像でしかなかったので、実際のカナダの方々の心みたいなものを伝えられるかなというのはありました」。

それでも来館者の反応はポジティブなものが多く、カナダの歴史があまり知られていない中で今回の展示では「本当に勉強になりました」という声が多かったという。「多様性社会というイメージを持っていたが、日本人も含めて差別された歴史があったことに驚いた」「アメリカへの移民は聞くがカナダにもそれほど多くの日本人が移民していることは知らなかった」といったものや、中にはカナダへの移民という局所的な事象にとどまらず、移民、差別、補償、さらには先住民族の権利など「社会全体の正義・公正にも触れているという意見や日本ではどうなのかなど自分事としてユニバーサルに捉えてみてくれているコメントもあり、作った側としては意図が伝わって本当にうれしかった」と語った。

パネルだけではなく、映像や実際の書類も閲覧できる会場。2025年10月2日、横浜市。撮影 三島直美

「今回の展示に関わらせていただいてすごくラッキーだったなと思います」と原本さん。カナダの資料がデジタル化され充実してきた中で今後につながると思うと期待している。できればカナダ人の「ジャスティス(公正)」に対する感覚に肌で触れてみたいとも語った。

「Broken Promises 破られた約束-太平洋戦争下の日系カナダ人-」3Dバーチャルツアーは2026年3月31日まで無料で利用できる。資料館に展示されているパネルを見られるほか、日本語のみのパネル部分には英語の解説がポップアップで見られるようになっており、動画や資料なども英語で閲覧できる仕組みなっている。

リンクはこちらから。https://my.matterport.com/show/?m=wBk7qKMNLzj&back=1

日系文化センター・博物館の「Broken Promises(英語)」のサイトはこちらから。https://centre.nikkeiplace.org/exhibits/broken-promises/

「Broken Promises 破られた約束」日本巡回展示実行委員会のサイトはこちら。https://brokenpromisesjapan.com/

講演会 After the Broken Promises 破られた約束のその後

講師:ジョーダン・スタンガー・ロス (Jordan Stanger-Ross) 氏(カナダ ビクトリア大学 歴史学教授 “Landscapes of Injustice”(不正義の風景)プロジェクトディレクター)

「海外移住資料館」について 独立行政法人国際協力機構(JICA)横浜センター内にあり、日本人の海外への移民について情報提供している。資料館の学芸担当研究員・小嶋茂さんに話を聞いた。

歴史を未来へつなぐ拠点「われら新世界に参加す」 海外移住資料館は2002年10月4日に、日本人の海外移住の歴史を日本人だけでなく、日系人、特に若い世代へ伝えることを目的として設立されたと説明した。資料館を設立するプロジェクトは2000年4月1日に正式に始動し、国内外の資料収集や展示構想の策定を経て開館に至ったという。

設立の背景にあったのは「移民」に対する誤った認識が日本にあったからだと振り返る。1980年代半ばから、中南米から日本人移民と日系人の出稼ぎ現象が起き多くが来日したことを契機に、国内で「日本人の顔をしているのに日本語を話さない」と言われるなど言語や文化の違いからさまざまな摩擦が生じたという。当時、日本の公的な教育では海外移住の歴史がほとんど扱われず「大勢の日本人がかつて海外へ移住していった」という事実すら広く知られていなかったというのが現実的にあった。

こうした状況を踏まえ、毎年開催されている海外日系人大会などで「移住の歴史を伝える施設を作ってほしい」という要望が繰り返し寄せられ、資料館設立へとつながったと説明した。

展示コンセプトは「われら新世界に参加す」 。これは「大阪の国立民俗博物館初代館長の梅棹忠夫先生が1978年にブラジルでの基調演説で提言されたコンセプトです」。民族学者の梅棹忠夫氏は、移民は「棄民」として捉えられることもあるが、実際には移住先の社会に参加し、貢献してきた存在であるという肯定的な視点を示した。小嶋さんは「『棄民』には『日本を捨てて行った人たち』と、『日本国から捨てられた人たち』という2重の意味がある」と説明。しかし、「(梅棹氏の)肯定的な捉え方をすべきであるというメッセージを受けて、資料館では移民とは移住先の国々における参加と貢献であるという視点から移住をお伝えするということで始まりました」。

常設展示は大きく分けて2つ。前半は、ハワイ移住から2000年までの日本人海外移住の歴史、後半はコンセプトを具体的に紹介する内容になっているという。移住の理由、渡航手段、生活やコミュニティ形成を、国別ではなくテーマ別に多角的に構成し、肯定的な理解を促している。最近は20周年を機にリニューアルが進められ、オンラインのデジタルコンテンツも充実を図っている。

日本でまだ誤解されていることが多い日本人移民だが、日系人が直接日本人を助けた例として、戦後直後の1946年から1952年にかけて日系人が中心となって展開された救援活動「ララ物資」を挙げた。第2次世界大戦中は、カナダやアメリカでは強制収容、南米でも敵性外国人扱いをされて、日系人も決して裕福ではなかったはずだが、ララ物資を通して日系人の日本への支援は現在の金額に換算すると約1200億円にもなるという。ララ物資全体の約20%を占めていたと説明した。日本人の6人に1人がララ物資の恩恵を受けたとされる。粉ミルクや毛布、薬などの支援は、戦後の困窮する人々の命を救った。「この活動が日系人主導であったことは広く知られていないですが、忘れてはいけないと思っています」。

日本人移民の歴史は、現代日本が外国人を受け入れる際の重要な示唆を与えるとも語る。偏見や摩擦は避けられないが、日系人は海外でそれを乗り越えてきた歴史があり、「そこから学ぶことはたくさんあると思います。そうしたアメリカ大陸に渡った日本人の歴史を学べるのがこの資料館です」。

海外日系人博物館の未来をつなぐ―ネットワークで再活性化を目指す 日本人移民の歴史を伝える博物館は北米や南米に数多く存在するという。しかし、南米ではその多くが設立後に関心を失い、来館者が減少し「幽霊博物館」と化してしまう現状を危惧していると話す。背景には、設立を担った1世・2世が高齢化し、次世代である3世・4世が十分に継承できないという課題がある。

こうした状況を打破するため「ネットワークによる連携と再活性化」を模索していると話す。「例えば、複数の館が協力して、祭りと食文化など共通のテーマで資料を整理し、パネル展示などで共同開催することで関心を呼び戻す取り組みが可能だと思っています。そうすれば来館者が異なる地域の展示に興味を持ち、ブラジルに行ってみようとか交流の機会が生まれることも期待されます」。

北米ではボランティア活動が比較的活発で一定の支援体制があるため、南米ほど深刻な幽霊博物館化は少ないという。「それでも3世ならば祖父母への関心があっても、5世6世と世代が進む中で関心の低下は避けられないと思いますし、そこを食い止めて大事な歴史を次の世代に伝えていくには連携ネットワークの力が重要だと思っています」。

今回の「Broken Promises」プロジェクトは博物館連携の新しい可能性を示したと語る。今後は「ブラジル、ボリビア、パラグアイ、アルゼンチンなどの博物館が連携し、みんなの力で活性化できないかを提案していきたいと思っています」と話した。

JICA横浜 海外移住資料館:https://www.jica.go.jp/domestic/jomm/index.html

「Broken Promises 破られた約束」のパネルの前で。左から、小嶋さん、原本さん、渡辺さん。2025年10月2日、横浜市。撮影 三島直美

(取材 三島直美)

合わせて読みたい関連記事