手仕事が紡ぐ、あたたかい贈り物。

2025年 11月15日(土)と16日(日)

10:00-17:00

日系文化センター・博物館 6688 Southoaks Crescent, Burnaby

入場料: 大人5ドル [18歳未満、65歳以上、NNMCC会員は入場無料]

80以上のクラフトと食べ物ブースが集います。無料のキッズコーナーやドロップイン・プログラムもお楽しみいただけます。

手仕事が紡ぐ、あたたかい贈り物。

2025年 11月15日(土)と16日(日)

10:00-17:00

日系文化センター・博物館 6688 Southoaks Crescent, Burnaby

入場料: 大人5ドル [18歳未満、65歳以上、NNMCC会員は入場無料]

80以上のクラフトと食べ物ブースが集います。無料のキッズコーナーやドロップイン・プログラムもお楽しみいただけます。

お問合せ:604-618-6491(テキスト可)、vjuc4010@gmail.com 牧師 イムまで

住所:4010 Victoria Dr, (Between 23rd and 25th Ave East), Vancouver

―――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

サレーNorthwood 合同教会 日本人会衆礼拝

11月16日(日)午後2時より。

住所:8855 156 St, Surrey, BC, V3R 4K9

お問い合わせ:604-618-6491(テキスト可)イム、kuniokazaki98@gmail.com 岡崎まで

2025年10月10日、バンクーバーにて日本カナダ商工会議所(Japan Canada Chamber of Commerce/JCCOC)の第22回年次総会(Annual General Meeting)が開催されました。今年も会員企業、個人メンバー、関係者が多数集まり、前年度の活動・会計報告、新年度の計画発表が行われました。

本会は2003年に設立されて以来、ビジネス・文化・教育・観光を通じて日本とカナダを結ぶ活動を続けており、今回の総会ではその歩みと未来への展望が力強く語られました。

会長挨拶

冒頭の挨拶では、6年間会長を務めたサミー高橋氏が登壇。会の歴史と設立者/初代会長である小松和子氏らの功績に触れながら、「JCCOCの使命は、ビジネスをはじめとする多様な交流を通じて日本とカナダをつなぐことにある」と改めて強調しました。また「今期は持続可能でより開かれた組織づくりのために、今後の体制と運営方針を見直す」と述べ、会員への感謝を述べました。

理事紹介

今年度の運営理事12名が紹介され、それぞれの役職が発表されました。会長はサミー高橋(Sammy Takahashi)、副会長にはケーシー 若林(Casey Wakabayashi)氏、疋田 拓也(Takuya Hikita)氏とウィットレッド 太朗(Taro Whitred)氏。その他に、入谷 伊都子(Itsuko Iritani)氏、宮鍋 健樹 (Kenki Miyanabe)氏、田尻 純一(Junichi Tajiri)氏、鈴木 美和(Miwa Suzuki)氏、吉川 英治(Eiji Yoshikawa)氏、加藤 真理(Mari Kato)氏、渡部 句美子(Kumiko Watabe)氏、悠治 マトソン(Yuji Matson)氏が理事として名を連ねています。名誉理事にはパトリシア・ベーダー – ジョンソン(Patricia Bader-Johnson)氏が紹介されました。

会計報告

会計担当の入谷氏より、2024年7月〜2025年6月期の財務報告が行われました。本年度も健全な財政運営が維持されており、主要な収入源は会費および各種イベントの収益であることが説明されました。支出は保険料、事務費、寄付金などが中心であり、朝日野球チームやニューウェストミンスター高校音楽プログラムへの寄付も実施されました。長期負債はなく、安定した財務運営が確認されました。

会員報告

2025年度の会員数は個人会員29名、法人会員28社、計57名。前年から引き続き増加傾向にあり、文化・教育・観光など多様な分野の会員が活動に参加しています。

活動報告

活動報告は宮鍋健樹氏より行われ、4期にわたる多彩な取り組みが紹介されました。

第1四半期(2024年7月〜9月)

税務セミナー、文化交流パフォーマンスの歓迎会、守口市(大阪)との姉妹都市高校バンド交流支援などを実施。また、「つなぐ塾」では年間を通して8回のセミナーと文化祭を開催しました。

第2四半期(10月〜12月)

お笑い芸人あらぽん氏によるひょうたんアート・ワークショップ、メンタルヘルスウェビナー、クリスマスパーティなどを実施。同パーティでは第4回 Kazuko Komatsu Award 授賞式が行われ、ケーシー若林氏と鈴木美和氏ら6名が表彰されました。

第3四半期(2025年1月〜3月)

リーダーシップ・ワークショップ、防災セミナー、全米ボクシング殿堂入りの吉川英治氏による特別講演などを開催。また、UBCとCareer-tasu との共催によるJapan Connect Fairには28社、500名以上が参加し、過去最大規模の成功を収めました。

第4四半期(4月〜6月)

早稲田大学長谷川教授による起業セミナー、居合道実演、戦後80年記念イベントなど文化・教育・社会貢献活動を展開。さらに、子ども向け創作ワークショップやネットワーキング交流会も実施されました。

監査済み財務諸表承認・理事承認

監査担当の悠治マトソン氏が登壇し、前年度の監査済み財務諸表が承認されました。続いて、2025-26年度の12名の理事体制が正式に承認されました。

新年度計画

副会長のウィットレッド太朗氏が新年度の展望を発表。今年は個々の理事による活動に加え、商工会主導のプロジェクトを強化していく方針を示しました。

主な計画として、Japan Connect, Career & Networking Fair(UBC学生団体との共催)、日加スタートアップ&投資カンファレンス(2026年6月予定)、パウエル街地域再生プロジェクト(Kintsugi Associationとの協働)などが挙げられました。これらを通じて、地域社会・文化・経済の架け橋としての役割をさらに強化することが期待されます。

閉会の挨拶

副会長の疋田拓也氏が登壇し、「急速に変化する時代の中で、柔軟さと確固たる価値観を両立させ、質の高い交流機会を創出していきたい」と力強く述べました。「皆さまのご支援のもと、JCCOCはさらに強く成長してまいります」と結び、第22回年次総会は盛会のうちに幕を閉じました。

懇親会

総会後のディナーでは、在バンクーバー日本国総領事館より経済担当領事、木山雅之氏が挨拶を行い、日加両国の経済協力とスタートアップ連携の重要性を述べました。

続いて、George Sim氏が自身の半世紀にわたる日本との交流をテーマにゲストスピーカーとして登壇。長年にわたり千葉市とノースバンクーバー市の青少年交流を通して姉妹都市活動に貢献してきた経験が紹介され、若者との文化交流にまつわる心温まるエピソードが共有されました。

最後にサミー高橋氏より、12月開催予定のパウエル街再生支援イベントやクリスマスランチなど、今後のイベント予定が共有されました。

おわりに

設立22周年を迎えたJCCOCは、日加両国の絆を深める懸け橋として、これまで培ってきた基盤をさらに発展させながら、より開かれた交流の場を築いていくことを確認しました。次年度も、持続的な成長とネットワークのさらなる広がりが期待されます。

著者: 西田珠乃

撮影: 乘峯良輔

寄稿: 日本カナダ商工会議所

合わせて読みたい関連記事

エドサトウ

映画『スマッシュマシン』が公開となり、それを見た友から「エドさん、主人公と一緒に出ていますよ」と連絡があった。この映画に出演したのは、もう一年も前のことで、この映画はどうなっているのか気になっていた時なので、息子と一緒にダウンタウンの映画館にでかけた。街路樹の並木道もすっかり色づき、朝から冷たい小雨が降る中、車で映画館に出かける。映画は12時半からだけれど、駐車場の心配もあり、早めに出かければ、まだ映画館は開いておらず、近くのコーヒーショップに寄り、コーヒーと昼食を兼ねた食事を食べていたら、瞬く間に時間は過ぎてしまい、慌てて映画館に戻ると、もう映画が始まるという時間であった。最初はスポンサーの広告の映像が流れていたが、まだ時間が早いのか席はガラガラであった。

ここ最近は、映画館で映画を楽しむことは無いので、きわめてエキサイティングな楽しい映画鑑賞の日であった。

映画はアメリカで有名なプロレスラーの物語で、彼が東京ドームでの格闘技の大会に出るために飛行機に乗ると、たまたま日本へ行く飛行機の中で席が隣同士で少しばかり会話をするという場面に僕が出てくるだけのことであるが、たまたま、運よく出演させてもらったということである。

この映画のオーディションを受けた時、多くのバンクーバーの日本人の方が来ていて、皆台本をもらい、熱心にセリフを覚えている様子であった。しかし、ぼくの貰った用紙にはセリフはなく、どうなっているのかと思い、係の人に聞けば、オーディションの時は、自己紹介などをしてくださいとのことであり、何も特別にすることもなく、順番を待っていた。たまたま、昔の友がいたので、「プロレスの映画だと、レスリング、特に女子の部はオリンピックで人気があるから、うまくゆけばヒットするかもしれないね!」などと話をしていた。

時間が来てオーディションの部屋に入ると大勢の人が仮のセットの回りにいた。僕は自己紹介のつもりで中に入ると、いきなり英語の台本を渡されて「これを覚えて、やってください」といきなりに言われて、様子が違うので、少々焦りだした。後で分かったことであるが、この映画の30代前と思われる若い監督が自ら相手役となり、オーディションの撮影をしたが、どうも英語の場面で、「R」の発音がうまくゆかないけれど、日本語の部分は、それなりうまくできて、自分なりに「まあまあかな?」と思っていたが、半年が過ぎても連絡もないので、少々あきらめてきたころに撮影の案内が来た。

当日は、夕方からの撮影予定なので、道が混む前の早めに郊外の現場に行くと、係の人が「今日はスケジュールが遅れているので、もう一度、後から来てほしい」と言う。そして、「この時間帯は撮影クルーの集合時間で、君はもっと後でいいよ」と言われて、少々不安となるが、一旦、自宅に戻り一休みをして、また撮影現場に行くと、車の駐車場所が無いので係の人に言うと、別の場所を用意してくれて、一安心をして近くのトレイラーハウスの役者の個室に落ち着き、用意してきた本などを読み始める。しばらくして用意されてあるスーツに着替えて待機していると係のADさんが来て、「撮影は予定より遅くなるので、先に食事(映画の世界ではランチというらしい)にしてください」と言う。となりの個室に、以前一緒に映画に出たKさんがいるので一緒にキッチンカーに行き食事をもらい、部屋で美味しくいただき、その料理の出来栄えに感心もしたりした。

となりの知人のKさんは、僕の後の撮影なので、彼と遅くまで世間話をしていたら、9時過ぎに声がかかり、撮影現場の控室に移動する。長い北国の夏の陽も暮れてすっかり真っ暗になった部屋の太い配線ケーブルが何本もころがる床をそろりと待合室に移動して、出番を待つ。やがて、ADさんに呼ばれて撮影現場のセットに行くと、監督が「エド、僕のことを覚えているか?」と声をかけてくれた。オーディションの時、僕の相手役をやった人なので良く覚えていたが、英語のセリフの「R」の発音に苦労したから、少しばかり快く思っていなかったが、オーディションの時、彼は役者かと思っていたが、ここに来たら、彼が映画監督で指示を出しているのは、意外であったが、彼のお陰で、また撮影にこれたと思えば、嬉しくもあった。

この日の撮影場面が映画に出てくるのであるが、人間のつながりは妙なものである。

撮影が終わり自宅に帰りついたのは、深夜の1時ごろであった。

投稿千景

視点を変えると見え方が変わる。エドサトウさん独特の視点で世界を切り取る連載コラム「投稿千景」。

これまでの当サイトでの「投稿千景」はこちらからご覧いただけます。

https://www.japancanadatoday.ca/category/column/post-ed-sato/

朝の空気は澄みわたり、庭先の植物の葉に白い粒が光ります。それが露から霜に変わる時、冬に向かっていくのを感じます。

グレーターバンクーバー界隈にお住まいの皆さまは、美しい紅葉を楽しまれていることでしょう。赤く染まる木々と夕焼け、そして雨のシーズンを迎える鼠色の空は、秋の終わりと冬の気配が重なり合います。

今年も住宅街やショッピングモールでは、ハロウィンの賑やかなディスプレイが目を楽しませてくれています。今年は、我が家に何人の子どもたちが訪ねて来てくれるでしょうか。

「Trick or Treat!」という元気な声が近所に響くと、平和のありがたさをしみじみと感じます。子どもたちの笑顔が、この街にも、世界にも、長く続いてほしいと願わずにはいられません。

一年の終わりを少しずつ意識しながら、穏やかな時間を積み重ねていきたいものです。

「フィルム撮影と着物」

私が初めてフィルム撮影で着付けの仕事をしたのは、20年ほど前の『FANTASTIC FOUR 2』という映画でした。日本の結婚式のシーンで、参列者の着付けを担当しました。

日系のサイトで着付師を募集しており、翌日の朝4時集合と知らされたのは、前日の午後10時のことでした。

着物に関しては、カナダにいても週に一度は自分で着ていますし、人に着付ける仕事も少しずつ始めていましたので、何とかなるだろうと思っていました。ですが、撮影の着付けや補助となると事情はまったく異なりました。

私は日本でもカナダでもドラマや映画の制作経験は全くなく、現場では右往左往してしまいました。

用意された着物や小物も十分に揃っておらず、これまでの知識と経験を総動員して、必死に着付けたことを覚えています。

それでも、十分な準備がない中でプロダクションが日本人の着付師を雇ってくれたことは、日本人としてとても嬉しく、誇らしく感じました。

北米で放送されるドラマや映画での着物のシーンはそう多くありません。ですが、日本人の皆さんが違和感なく観られ、作品のストーリーに集中できること、それが衣装部で着物を担当する者の使命だと思っています。

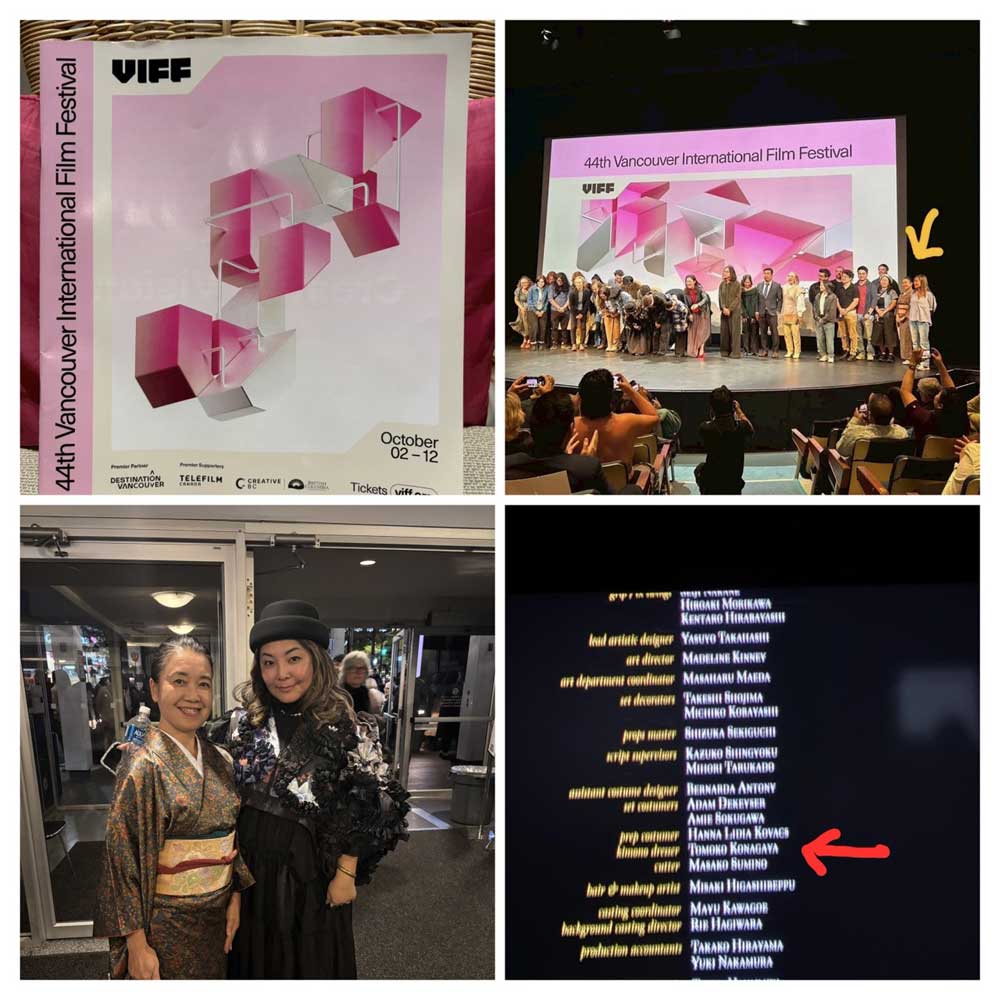

その後、昨年放送された『SHOGUN』を含め、いくつかの作品で着付けを担当し、2年前には『AKASHI』という作品に着付師として参加しました。この作品は今月開催されたバンクーバーフィルムフェスティバルで上映されました。

撮影はバンクーバーと東京で行われ、カナダ人と日本人の俳優やクルーが合同で制作しました。日本で活躍されている俳優やクルーの皆様と関われたことは、大変貴重な経験となり、勉強になりました。

普段、お寺での着付けとは異なり、撮影現場での着付けは全く別のものです。作品の中で着物が持つ意味は深く、衣装はその人物が言葉を発しなくても背景や性格を表す重要な道具です。

着付けの仕事をするたびに、「こうすればよかった」「あのときの判断は適切だったのだろうか」と振り返ることが多くあります。

反省と学びを重ねながら、少しでもより良い仕事ができるよう努めている日々です。

近年、バンクーバーで撮影に関わるお仕事をされる方も増えているかと思います。通い慣れた道が映画の中で他の街として登場したり、知り合いがエキストラで映っていたりするのは、日本では味わえない楽しみです。

秋の夜長には、バンクーバーで撮影された作品をゆっくり観るのも良いかもしれません。

*参照*

暦生活

https://www.543life.com

霜始降しもはじめてふる:氷の結晶である、霜がはじめて降りる頃。昔は、朝に外を見たとき、庭や道沿いが霜で真っ白になっていることから、雨や雪のように空から降ってくると思われていました。そのため、霜は降るといいます。

VIFF

https://viff.org

日加トゥデイの記事から

VIFF日本映画特集「映画ならではの多様な日本文化に触れる」

映画「あかし」がVIFFでワールドプレミア!吉田真由美監督インタビュー

「国宝」と「あかし」VIFF2025観客賞を受賞

AKASHI

https://viff.org/whats-on/viff25-akashi

「着物語り」

コナともこさんが着物の魅力をバンクーバーから発信する連載コラム。毎月四季折々の着物やカナダで楽しむ着こなしなどを紹介します。

2020年8月から連載開始。第1回からのコラムはこちらから。

コナともこ

アラ還の自称着物愛好家。日本文化の伝道師に憧れ日々お稽古に励んでおります。

14年前からコキットラム市の東漸寺で「和の学校」を主宰。日本文化を親子で学び継承する活動をしております。

年間を通じて季節の行事に加え、お寺での初参り、七五三祝い、十歳祝い、元服祝い、二十歳祝い、結婚式、生前葬、お葬式などの設えと装いのお手伝いもさせていただいております。

*詳しくはコナともこ までお問い合わせ下さい。tands410@gmail.com

東漸寺は非営利団体で、和の学校の収益は東漸寺の活動やお寺の維持の為に使われています。

カナダ人の夫+社会人と大学生の3人娘がおり、バンクーバー近郊在住。

和の学校ホームページ https://wanogakkou.jimdofree.com/

インスタグラム https://www.instagram.com/wa_no_gakkou_tozenji/

フェイスブック https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100069272582016

東漸寺Tozenji Temple https://tozenjibc.ca/

コナともこ

Facebook https://www.facebook.com/tomoko.kona.98

Instagram https://www.instagram.com/konatomoko/?hl

今年もインフルエンザ・COVIDの予防接種のピークシーズンがやって来ました。皆さんは、もう接種を受けられましたか?

私の薬局では今年は少し特殊な状況が生まれています。ギブソンズには2軒の薬局がありますが、そのうち1軒が「人手不足のため、一切の予防接種を行いません」と宣言しました(と患者さんが教えてくれました)。さらに、毎年恒例だったパブリックヘルスユニットによる集団接種も見送りとのこと。つまり、私が勤務するロンドンドラッグスが町で唯一の接種拠点という形になってしまったから大変です。

これはビジネス的には追い風に見えるかもしれませんが、現場は人手と時間のやりくりが勝負です。予防接種業務自体は、過去16年間も続けてきたので目新しいことはありませんが、これまで他の場所で接種を受けていた方々が一気に私の薬局に流れてくるとなれば、例年以上に気を引き締めて臨む必要があります。

ただ、人の気合いで仕事が回っていたのは昔のこと。最近では、人手不足を補い、薬剤師が専門性に集中できるよう、薬局のDX(デジタルトランスフォーメーション)が加速しています。私の店舗でも、この1、2年の間にいくつかのシステムが導入されましたので、紹介したいと思います。

まず、お薬の用意が完了した際にテキストメッセージ(SMS)を送る機能です。従来は、希望する患者さんにお薬ができた旨を電話でお知らせしていたものが、テキスト送信で済むようになり、この作業は1秒もかかりません。薬局が患者さんに電話をかける時間を節約し、逆に患者さんが「お薬できていますか?」と確認の電話を入れる手間の両方が省け、双方の負担が軽減し、利便性が向上したと思います。

また、セントラルフィル(Central Fill)というシステムも取り入れられました。店舗で入力・監査まで行った処方データを、本社にある大規模調剤センターに送り、機械が計数・包装・ラベル貼付までを行います。調剤済みの薬が店舗に送られたのち、最終照合して患者さんに渡すという流れで、いわば社内アウトソーシングです。

ブリスターパック(朝・昼・夕・就寝の仕切り包装)の作成には、10年以上前からセントラルフィルが利用され、「機械で作る+スタッフが目視で確認する」の二重チェックで運用してきました。しかし、昨年新たに本社に導入されたマシーンでは、画像認識機能によるコンピューター監査が行われるようになりました。具体的には、原薬ボトルのバーコードで薬品名、規格、ロット、有効期限を照合し、各マス目の錠剤はカメラ画像で形と色、薬の数を自動判定します。どこかに不一致があれば機械が自動停止し、スタッフが再確認します。

最近は、これに加えてバラ錠を正確に数えてバイアルに充填する巨大な自動調剤機もセントラルフィルで稼働を始めました。患者さんが、電話やアプリでオーダーしたリフィル処方せんを、セントラルフィルの自動調剤機で調剤し、翌日には薬が用意できるという仕組みが出来上がりました。店舗レベルでは患者さんの対応により多くの時間を割くことができ、また反復的な計数作業の量を減らすことにつながっています。

もちろん、すべての薬がセントラルフィルで調剤されるわけではありません。当日ピックアップ、調製・混合が必要な薬、冷蔵・冷凍品、麻薬などの規制薬、在宅向けの細かなオーダーなどについては、店舗レベルで対応していますのでご心配なく。

最後に、お薬保管場所検索システムです。これは準備済みのお薬に専用クリップを装着し、ピックアップ時に患者さんの情報を入力すると、該当の薬が光や音で所在を知らせてくれます。これで薬局スタッフが「できている薬を探す時間」を大幅に短縮。バーコード照合で薬の取り違いも未然に防げ、またレジ前での待ち時間が減りますから、スタッフと患者さん双方のストレスを軽減できます。

これらの工夫は、薬剤師が本来担う相談・服薬指導・予防接種に集中できる環境づくりに直結します。ピックアップのワークフローを最適化すると、エラーが減ってスピードが上がり、最終的にサービスの質を上げることができます。DXは時間を生む強力な味方で、私自身この流れが大好きです。人とテクノロジーが協働することで、大量の処方を正確かつ効率的に処理し、患者さんの声に耳を傾ける時間を増やすことができるからです。

今後私が楽しみにしているのは、AIによる処方入力支援と問題検出です。日本では一足先にQRコードで処方せんの内容をコンピューターに取り込むシステムが普及していますが、ここはカナダでも追いつきたい領域です。さらなるDXにより薬物治療上の問題を素早く見つけて解決し、より安全で満足度の高い治療に貢献できれば、薬剤師としては本望です。もちろん、テクノロジーの進化に置いていかれないよう、私自身もアップデートを続け、また予防接種も頑張っていきたいと思います。

*薬や薬局に関する一般的な質問・疑問等があれば、いつでも編集部にご連絡ください。編集部連絡先: contact@japancanadatoday.ca

佐藤厚(さとう・あつし)

新潟県出身。薬剤師(日本・カナダ)。 2008年よりLondon Drugsで薬局薬剤師。国際渡航医学会の医療職認定を取得し、トラベルクリニック担当。 糖尿病指導士。禁煙指導士。現在、UBCのFlex PharmDプログラムの学生として、学位取得に励む日々を送っている。 趣味はテニスとスキー(腰痛と要相談)

お薬についての質問や相談はこちらからお願い致します。https://forms.gle/Y4GtmkXQJ8vKB4MHA

全ての「また お薬の時間ですよ」はこちらからご覧いただけます。前身の「お薬の時間ですよ」はこちらから。

ノーザンスーパーリーグ(NSL)初代チャンピオンの座をかけて11月からプレーオフが始まる。今年開幕したカナダ女子プロリーグは6チームで、上位4チームがプレーオフに進出。バンクーバーを本拠地とするバンクーバー・ライズFCは3位でレギュラーシーズンを終え、2位のオタワ・ラピッドFCと対戦する。

ライズには今年7月から加入した岡本祐花選手が所属する。初めての海外チームでプレーオフ進出となった岡本選手は、日本ではプレーオフという制度がなかったため、「緊張感を持ったプレーオフの試合は大学生の時以来とかなので、すごいワクワクしてます」と今から楽しみにしていると言う。

現在は、プレーオフ第1戦に向けてチームとして練習をする中、岡本選手自身は「攻撃の面で勝たないといけない試合が続くと思うので、いかにゴールに近づけるかが大事だと思っていて、クロスとかが上がるタイミングとかにフォーカスして今は練習をやっています」と話す。ポジションはディフェンダーだが、攻撃時にはゴール前に上がってシュートも放つ。フィジカルが強い選手が多い中で「なるべく捕まらないように」とうまくかわしていると笑う。

「ここ(バンクーバー)に来るって決めた時から、本当に最初のリーグチャンピオンになりたいっていう思いは持ってきたので」と思いは強い。レギュラーシーズン首位は逃したが、「プレーオフでチャンピオンになれるチャンスが残ってるので、本当にチャンピオンになれるようにみんなでがんばりたいです」と語った。

NSLプレーオフは11月1日にモントリオール(Stade Boréale)で、AFCトロント(1位)とモントリオール・ローゼズFC(4位)で開幕。4日にバンクーバー(Swangard Stadium)でライズとラピッドが対戦する。

ホーム&アウェイで、11月8日にはオタワ(TD Place)でライズ対ラピッドが、9日にトロント(York Lions Stadium)でAFCトロント対ローゼズが対戦する。トロントには木﨑あおい選手が所属している。決勝は11月15日。NSL初代チャンピオンが決定する。

全試合、CBCもしくはTSNで中継される。https://www.nsl.ca/

プレーオフ日程(時間は現地時間)

11月1日 12pm モントリオール対トロント

11月4日 7pm バンクーバー対オタワ

11月8日 3pm オタワ対バンクーバー

11月9日 2pm トロント対モントリオール

(取材 三島直美)

合わせて読みたい関連記事

2025年は戦後80年であり、被爆80年でもあります。第二次世界大戦は終戦を迎え今年で80年と言われていますが、被爆者にとってはどうでしょうか。被爆二世や三世の中には、医学的には証明させていませんが、癌や心臓病などを抱えそれが一世の被爆の影響ではないかと不安を抱きながら生きている人たちが大勢います。差別を恐れて、自分が被爆者であることを隠してきた一世に続いて、二世三世も自分の生い立ちの一部を未だ公表していない人たちも大勢いるのです。

2023年にテレビ朝日の「報道ステーション」初代統括プロデューサーである上松道夫監督が、祖父鈴木照二、母鈴木カオル、娘万祐子のインタビューを中心としたドキュメンタリー映画「ある家族の肖像~被爆三世代の証言~」を制作されました。

鈴木照二は、旧制広島高等学校の在学中に広島で被爆、その娘である被爆二世は高校時代から体調を崩します。そして三世である孫は、大学生4年生の夏に甲状腺癌の告知を受けます。3世代が戦争や原爆についてそれぞれの想いを語ると共に、未来をどのように生きていきたいと思っているかを語っています。三世代が共に広島を訪れるロードムービーです。

自主映画として上映していますが、是非たくさんの方々に見ていただき、原爆の影響、被爆者の苦悩や不安、不安と共生していく未来を観ていただけたらと思います。今回の上映イベントには、映画の音楽を提供したジャズピアニスト金谷康佑のピアノ演奏と映画に登場している被爆二世である母、鈴木カオルが上映後にトークショーを行います。是非、たくさんの方々にお越しいただきたいです。よろしくお願いいたします。

上松道夫監督作品 58分Blu-ray上映

【あらすじ】

2023年5月、ある家族三世代が神戸から旅に出た。目的地は祖父の被爆地・広島

78年前の薄れゆく“記憶”を取り戻すために…

凄惨な体験をした地で、果たして祖父・鈴木照二は何を思い出し、何を語るのか?

そして被爆二世である母・カオル、三世である娘・万祐子は、何を感じるのか?

カメラの前で、被爆三世代がそれぞれの思いを紡いだ…

祖父・鈴木照二さん(取材時95歳 被爆一世)

昭和20年8月、旧制広島高等学校1年在学時、勤労動員先の寮内で、原爆に遭遇。大きなけがはなかったものの、翌日から1週間、帰らぬ学友の姿を求めて爆心地付近を捜索。京橋川の河畔で凄絶な地獄絵を見た。長年、体内に悪性腫瘍をかかえており、孫にも被爆の影響が出たのではないかと案じている…

母・鈴木カオルさん (取材時64歳 被爆二世)

高校生の時、心臓に異常が発見され体調不良の日々を過ごす。 結婚し一女を出産。その後も甲状腺の機能低下や、原因不明の症状に悩まされている。愛娘に甲状腺ガンが発見され、ショックを受ける。福島の原発事故で避難を余儀なくされた子どもたちを、サマーキャンプに招待するボランティアに参加したことから、平和活動を推進することを決意。 ピアニスト・金谷康佑とともに平和のイベントを赤字覚悟で主宰している。

一人娘・万祐子さん (取材時26歳 被爆三世)

たった一人の孫娘で、祖父から可愛がられた。 大学で軽音学部に所属し、ギターとヴォーカルを担当。卒業ライブを控えた四年次の7月、検査で甲状腺ガンが発見された。 医師から「甲状腺の全摘手術で声帯を傷つけるかもしれない。手術の日までに一生分の歌を歌っておくように」と言われた。4カ月後の手術当日、喉を広く切開しリンパも切除する大手術に臨んだ。果たして手術は成功し、再び歌うことができるようになるのか…

朗読・斉藤とも子(女優)

2023年4月22日、広島のライブ・ジュークで行われた女優・斉藤とも子の朗読と、ジャズピアニスト・金谷康佑のコラボレーションをノーカット収録。爆心地近くで被爆し、小頭症児を出産したある被爆者の原爆症認定裁判での“陳述”を、斉藤とも子が渾身の朗読。恐ろしい原爆の実相と被爆者が背負わされた過酷な運命に胸を震わされる。

音楽・金谷康佑

ジャズピアニスト・作曲家。兵庫県出身、立命館大学卒業。関西を中心に活動。金谷康佑のオリジナル・アルバム『LYRICISM』から、「気だるい午后のワルツ」「邂逅」「私のこの人生」「家族の肖像~セピア色の寫眞~」など…澄んだピアノ・ソロが、ドキュメンタリー全編を彩る。2023年から、女優・斉藤とも子の朗読と共に「地球・平和、そして未来へ」と題したライブ活動を各地で行なっている。鈴木カオルと中学生時代の同級生。

撮影・編集・監督 上松道夫

1948年生まれ。1972年、テレビ朝日入社。数々の報道番組を制作。「報道ステーション」初代エグゼクティブプロデューサー。テレビ朝日退職後、フリーランスとしてドキュメンタリー制作を継続。2018年、テレメンタリー『追跡・原爆影響報告書』が、アジア・テレビジョン賞最優秀ドキュメンタリー番組にノミネート。2021年『ラストメッセージ“不死身の特攻兵”佐々木友次伍長』発表。映画雑誌「キネマ旬報」2024年ベストテンの文化映画部門で、奥村賢選考委員より1位に選出される。

2025年11月11日、午前10:30よりスタンレーバーク内にある日系人戦没者慰霊碑前(水族館近く)にて式典が行われます。NNMCCのYouTubeチャンネルでもリアルタイムでご覧いただけます。https://youtube.com/live/z28YptMW-Aw

セレモニー後にスタンレーパーク内のVancouver Rowing Clubでレセプションが行われます。どちらもご自由にご参加ください。

イベントウェブサイト:https://centre.nikkeiplace.org/events/remembrance-day-2025/

トロント・ブルージェイズがアメリカンリーグ優勝決定シリーズ(ALCS)を制し、ワールドシリーズ(WS)に進出した。10月20日にトロントで行われた第7戦の劇的な逆転勝利に、カナダはまだどことなくザワザワしているが、24日からいよいよWSが始まる。

相手はスーパースター軍団のロサンゼルス・ドジャーズ。大谷選手を筆頭に3人の日本人選手がいることから日本でも大注目のシリーズにトロントが脚光を浴びている。

ブルージェイズは、モントリオール・エクスポズがアメリカ・ワシントンDCに移ってからカナダで唯一の大リーグチームということもあり、カナダのチームとして全国にファンがいる。

特にバンクーバーはブルージェイズファンが多い。ALCSは隣州アメリカ・ワシントン州シアトルのマリナーズとの対戦となった。レギュラーシーズンでもマリナーズ戦にはバンクーバーから多くのブルージェイズファンが詰めかける。車で約3時間。ALCSでもかなり行っていたとスポーツ局が伝えていた。

バンクーバーにブルージェイズファンが多い理由は、カナダ国内でも野球が盛んな街なこと、そして、ブルージェイズ傘下のマイナーリーグHigh-Aバンクーバー・カナディアンズの存在がある。

WS第1戦で先発するトレイ・イエサベージ投手は今年5月20日にはバンクーバーで投げていた。4回先発しただけでAAに昇格し、8月中旬にはAAAに昇格。そして9月に大リーグでデビューしてWSに先発するという驚異的な22歳。バンクーバーはもちろん通り過ぎるだけだが、それでもバンクーバーでは若い成長していく選手たちを応援し、ブルージェイズを応援する。

チームをここまで率いたジョン・シュナイダー監督もバンクーバーで2014年、15年シーズンに指揮を執っていた。シュナイダー監督自身、優勝を決めた20日の記者会見ではバンクーバーからも祝福の声が届いたことを喜んでいた。

それ以外にも調整を兼ねてバンクーバーでプレーする選手も少なくなく、バンクーバーのファンは成長していったブルージェイたちを見守り続けているというわけだ。

32年ぶりのWS進出で沸くトロント、そしてカナダ。相手は昨季のWS覇者ドジャーズ。超強力打線には大谷選手、投手では山本、佐々木両投手と日本人選手の活躍が目立つ。トロントには現在日本人選手はおらず、スタッフで昨季まで日本ハム・ファイターズにいた加藤豪将さんがいるのみ。

だが、ブルージェイズにもこれまで日本人選手はもちろんいた。投手としては、大家投手や五十嵐投手が活躍した。しかし、最も人気だったのはなんといっても、川﨑宗則選手だ。元日本代表という野球センスと底抜けに明るいキャラクターでカナダの野球ファンを虜にした。当時のチームメートはスポーツネット(ブルージェイズ専門スポーツ局)に「彼の言っている言葉は一言も分からないが、彼の言っていることは理解できるんだ」と語っていた。

カメラを向けられるとマイクを奪って、チームメートすら分からない英語をテレビに向かって話す。そんなちょっとおどけたキャラクターでも、試合では堅実なプレーで内野を守る。そのギャップも良かったのかもしれない。バンクーバー・カナディアンズを観戦に来る白人男性でさえ、「Kawasaki」のユニフォームを着ていた。応援している子どもにカメラを向けて「誰のファン?」と聞くと、「Kawasaki」と返ってきた。もちろんメディアも川﨑選手にマイクを向けた。

ブルージェイズに来る前はマリナーズに所属していたが、それほど大人気ということは聞いたことがない。物おじしない明るいキャラがカナダの野球ファンに受け入れられたことは間違いない。野球という枠を超えてブルージェイズファンに愛された日本人選手だった。

24日から始まるWS第1戦。日本ではぜひ川﨑さんにブルージェイズの魅力を語ってもらいたい。

(記事 編集部)

合わせて読みたい関連記事

カナダでは、トロント国際映画祭とバンクーバー国際映画祭が盛況のうちに幕を閉じ、今年も多くの良作が上映されました。今回ご紹介する「グッドニュース(Good News)」(ビョン・ソンヒョン監督)は、トロント国際映画祭でプレミア上映され話題となった韓国作品で、1970年代に実際に起きた航空機ハイジャック事件をモチーフにした、社会派ブラックコメディです。

あらすじ:物語は、日本から北朝鮮への亡命を企てる過激派グループの青年たちが、民間航空機をハイジャックするところから始まります。事件を受け、韓国の中央情報部は正体不明のフィクサーを投入し、極秘作戦を計画。日韓両国の政府高官たちは世論操作と情報戦に奔走し、事件を都合よく作り替えようとします。報道統制、対外プロパガンダ、そして捜査の混乱などが次々と描かれ、事態は予想外の方向へと展開していきます。

物語は序盤からテンポよく進み、登場人物たちの会話にはユーモアと皮肉が巧みに織り込まれ、シリアスなのに思わず笑ってしまうシーンが多くあります。情報のねじ曲げや責任の押し付け合い、政治的駆け引きなどが、リアルさと可笑しさの絶妙なバランスで描かれています。

例えば、どう見ても混乱状態なのに、「これは我々の勝利だ」と言い張る官僚たちや、何かを言っているようで実は何も言っていない官僚の言葉の数々など、国家の威信、メディアの圧力、そして登場人物たちの都合や打算が入り乱れ、観ている側は笑っていいのか戸惑いながらも、つい吹き出すシーンがたくさん。

脚本の良さはもちろんですが、作品の最大の魅力は俳優陣の力強い演技です。火消し専門の裏の男として登場し、ミステリアスなのにどこか可笑しさも感じさせるソル・ギョング、ハイジャック犯のリーダーを冷静かつ狂気を秘めて演じる笠松将、誠実な韓国の将校を演じるホン・ギョン、日本の運輸政務次官として登場し政治の駆け引きと滑稽さを演じた山田孝之など、それぞれ自分の役割に誠実に取り組む人物をリアルに、かつコメディとしての面白さを損なわずに演じていました。

「グッドニュース」は、実話をベースにした重い題材をユーモアたっぷりに描き切った、韓国映画らしい社会派エンターテインメントです。笑いと皮肉を交えながら「国家」、「メディア」、そして「真実」のあり方に鋭く切り込んでいきます。笑った後に、「これ実話ベースなんだ」と考えさせられる、見ごたえのある作品でした。

10月17日からNetflixで配信開始となりました。

Lalaのシネマワールド

映画に魅せられて

バンクーバー在住の映画・ドラマ好きライターLalaさんによる映画に関するコラム。

旬の映画や話題のドラマだけでなく、さまざまな作品を紹介します。第1回からはこちら。

Lala(らら)

バンクーバー在住の映画・ドラマ好きライター

大好きな映画を観るためには広いカナダの西から東まで出かけます

良いストーリーには世界を豊にるす力があると信じてます

みなさん一緒に映画観ませんか!?

カナダ・バンクーバー市で10月2日~12日まで開催されたバンクーバー国際映画祭(VIFF)は17日に観客賞を発表。日本映画では、「国宝」と「あかし」が選ばれた。

第44回となる今年は、106,000人以上が参加し、約590回の上映、セッション、トークイベント、ライブショー他のイベントが行われたという。

観客賞は、VIFFの長編映画11部門で観客から選ばれた各部門1作品を表彰。受賞作品は11日間のフェスティバル期間中に5万票以上の投票によって選ばれた。

VIFFエグゼクティブ・ディレクターのカイル・フォストナー氏は声明で、「今年のVIFFは記念すべき年となりました。2025年はここ数年で最大規模のフェスティバルとなり、上映数や会場数が拡大し、観客数も増え、さらに新たな国際的パートナーシップも誕生しました」と振り返った。

「国宝(Kokuho)」(李相日監督)はGalas & Special Presentations部門で、「あかし(Akashi)」(吉田真由美監督)はNorthern Lights部門で受賞した。全部門の受賞作品は以下の通り。

Galas & Special Presentations

Kokuho, dir. Sang-il Lee

Showcase

In the Room, dir. Brishkay Ahmed

Panorama

Meadowlarks, dir. Tasha Hubbard

Vanguard

Gazelle, dirs. Nadir Saribacak, Samy Pioneer (Selman)

Northern Lights

Akashi, dir. Mayumi Yoshida

Insights

Free Leonard Peltier, dirs. Jesse Short Bull, David France

Spectrum

Khartoum, dirs. Anas Saeed, Rawia Alhag, Ibrahim Snoopy, Timeea Mohamed Ahmed, Phil Cox

Portraits

The Essence of Eva, dirs. Alex Fegan, Malcolm Willis

Altered States

Fucktoys, dir. Annapurna Sriram

Spotlight on Korea: The New Breed

3670, dir. Park Joon Ho

Focus: Edges of Belonging – Tales of Grit and Grace from India

Bad Girl, dir. Varsha Bharath

(記事 編集部)

合わせて読みたい関連記事